I’ve been a fan of James Tenney for a long time, but recent circumstances have returned him to the forefront of my mind. This has largely been due to the efforts of my friends Alexander Bruck (the avant-garde viola player based in Mexico City) and Juan Sebastián Lach Lau (the composer and synthesist based in Morelia). Since I arrived in Mexico, in individual efforts and within the collaborations of Ensemble Liminar, both have showed remarkable dedication to the composer’s legacy – instigating talks and a regular stream of performances of his often neglected body of work. I can’t explain how lucky I feel to have encountered both of these remarkable voices, and to have been offered the chance to hear Tenney’s work performed so many times in such a short period.

Within the history of American avant-garde music, there are few individuals more important than Tenney – not only through his own compositions, but also through his dedication to and support of others. When you chart his connections across various disciplines of creative practice (before, during, and after his lifetime) he’s everywhere. Strangely his name remains largely unknown, and even when it is, the scale of his contribution is usually grossly under-recognized. It’s confounding.

Tenney’s legacy operates on two fronts. He was an incredibly important composer. His works remain among the best created by his generation, but his actions often extended well beyond what he wrote, allowing him to become a kind of cultural bridge. 20th century composition was marked with strong personalities, many of whom, in the instances they came into contact, did not get along. Similarly, their works tend to be singular, uncompromising, and resist dialog with others. Tenney is the thread that joins them. He was a student of Carl Ruggles, John Cage, Harry Partch, and Edgard Varèse, remained close to all of them, and often performed in both Cage and Partch’s ensembles. He collaborated, or played, with Max Neuhaus, La Monte Young, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Malcolm Goldstein, Philip Corner, Michael Snow, Terry Riley, and countless others. He was close with Conlon Nancarrow, fervently supported the legacy of Charles Ives, and taught an entire generation of composers, not the least of whom was Charlemagne Palestine. Shockingly it doesn’t stop there. He was married to Carolee Schneemann for many years, and appeared in a number of her notable films and live works (including Meat Joy, and Fuse). He was close with Stan Brackage, as well “starring” in and scoring a number of his films. He was also a member of Fluxus. The breadth of his output and collaboration is astounding.

History and criticism tend to like to tie things into neat packages. Tenney’s output defies this. Without detracting from their value, when looking at the efforts of most of the prominent composers working during his lifetime – Cage, Partch, Nancarrow, Young, Reich, Glass, Riley, etc, a good critic could sum up the major themes within a couple of sentences. With Tenney this would be impossible. His output skirts into (and often combines) computer music, indeterminacy, generative systems, chance, microtonality, minimalism, synthesis, tape-music, and on. In other words, nearly all of the central conceits used by avant-garde composers during the second half of the 20th Century. Most were satisfied with one or two. Tenney was not. Despite the remarkable cohesiveness he achieved within this sprawling body of ideas, summing up his output becomes a significant task for anyone approaching it analytically. Though far from excusing it, this might explain his enduring neglect. It’s not that listeners find him hard to approach, critics do. As a result, people are rarely offered the chance to discover him, placing his legacy in the shadows with devoted fans of avant-garde music. This is made more tragic by the fact that, despite the complexity of its ideas, Tenney’s work is remarkably accessible. It only takes listening to enter its joys. To sum up his life, connections, collaborations, and body of work, in a single sentence – he was a breaker of barriers, those dividing us from him, are not his own.

During the late 60’s, after his marriage with Schneemann dissolved, Tenney found himself on the West Coast teaching at Cal-Arts, and in regular collaboration with two of my favorite neglected figures of the period – the harpist Susan Allen, and the artist Allison Knowles. In 1971 (with the assistance of Knowles and Marie McRoy) he completed a project begun in 1965 – The Postal Pieces. This small body of work offers deep insight into the dualities of Tenney – particularity his use of sound to develop consciousness in (or of) others. The works have humorous origins. Tenney had a lot of friends, but hated writing letters. As a substitute, he conceived of sending short scores on the back of postcards. The works focus on three themes – his idea of Swell form (utilizing repetition and progressing through a structurally symmetrical arch), intonation, and the desire to produce “meditative perceptual states.” He also spoke at length of his hope that a listener would be able to discern these structures early in a work’s performance, predict where they would go, and subsequently gain insights that would enable a new consciousness within the music. This is a very generous position – placing the listener first. Tenney’s generous tendency is also mirrored within the work’s titles. Each is composed and dedicated for a friend – John Bergamo, Allison Knowles, Pauline Oliveros, La Monte Young, Harold Budd, Philip Corner, Joel Krosnick, Buell Neidlinger, Susan Allen, Max Neuhaus, and Malcolm Goldstien. Not only is this a lovely nod, drawing attention to peers less recognized than himself (how times change), but the conceit of composing for others is always a generous act in its own right. Given the diversity of those represented, they also display the vast range of Tenney’s abilities. Rather than describe each work, I always prefer to point to the music itself. With each score, I’ve included a recording. These are dawn from New World’s wonderful release of The Postal Works. I hope you’ll consider supporting their work and pick it up. With that, I leave you with the scores and sounds of the great man himself. May he forever linger in your mind.

James Tenney – Having Never Written a Note for Percussion, for John Bergamo (1971)

James Tenney – Having Never Written a Note for Percussion, for John Bergamo (1971)

James Tenney – Swell Piece For Allison Knowles, Swell Piece #2 For Pauline Oliveros, and Swell Piece #3 La Monte Young (1971)

James Tenney – Swell Piece, For Allison Knowles (1971)

James Tenney – Swell Piece #2, For Pauline Oliveros (1971)

James Tenney – Swell Piece #3, La Monte Young (1971)

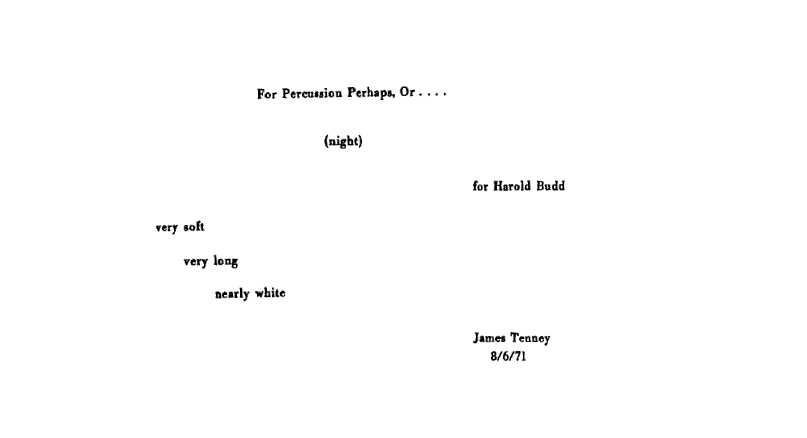

James Tenney – For Percussion Perhaps, Or (night), For Harold Budd (1971)

James Tenney – For Percussion Perhaps, Or (night), For Harold Budd (1971)

James Tenney – A Rose Is a Rose Is a Round, For Philip Corner (1971)

James Tenney – A Rose Is a Rose Is a Round, For Philip Corner (1971)

James Tenney – Cellogram, For Joel Krosnick (1971)

James Tenney – Cellogram, For Joel Krosnick (1971)

James Tenney – Beast, for Buell Neidlinger (1971)

James Tenney – Beast, for Buell Neidlinger (1971)

James Tenney – August Harp, For Susan Allen (1971)

James Tenney – August Harp, For Susan Allen (1971)

James Tenney – Maximusic, For Max Neuhaus (1965)

James Tenney – Maximusic, For Max Neuhaus (1965)

James Tenney – Koan, For Malcolm Goldstein (1971)

James Tenney – Koan, For Malcolm Goldstein (1971)

-Bradford Bailey