Peter Moore – Publicity photograph for 3rd Annual New York Avant-Garde Festival, August 26, 1965. Left to right: Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Takehisa Kosugi, Gary Harris, Dick Higgins, Judith Kuemmerle, Kenneth King, Meredith Monk, Al Kurchin, Phoebe Neville.

Writing on Nam June Paik’s Good Morning, Mr. Orwell recently, which, among many others, features Charlotte Moorman, has left the long neglected cellist lingering in my mind. Moorman, who died in 1991 at the the age of 57, is a figure from history that nearly everyone in the art world and avant-garde music community has encountered, yet few know much about. She is an image – an abstraction to which little is bound. Sometimes referred to as the Jeanne d’Arc of new music (a distinction coined by Edgar Varèse), and often simply as the topples cellist, Moorman was Julliard trained musician of the highest order – beginning her professional career with the American Symphony Orchestra. At the outset of the 1960’s, her roommate Yoko Ono began to encourage her toward the wild avant-garde efforts of Fluxus – the effect of which would change her life and bring her into wide public view.

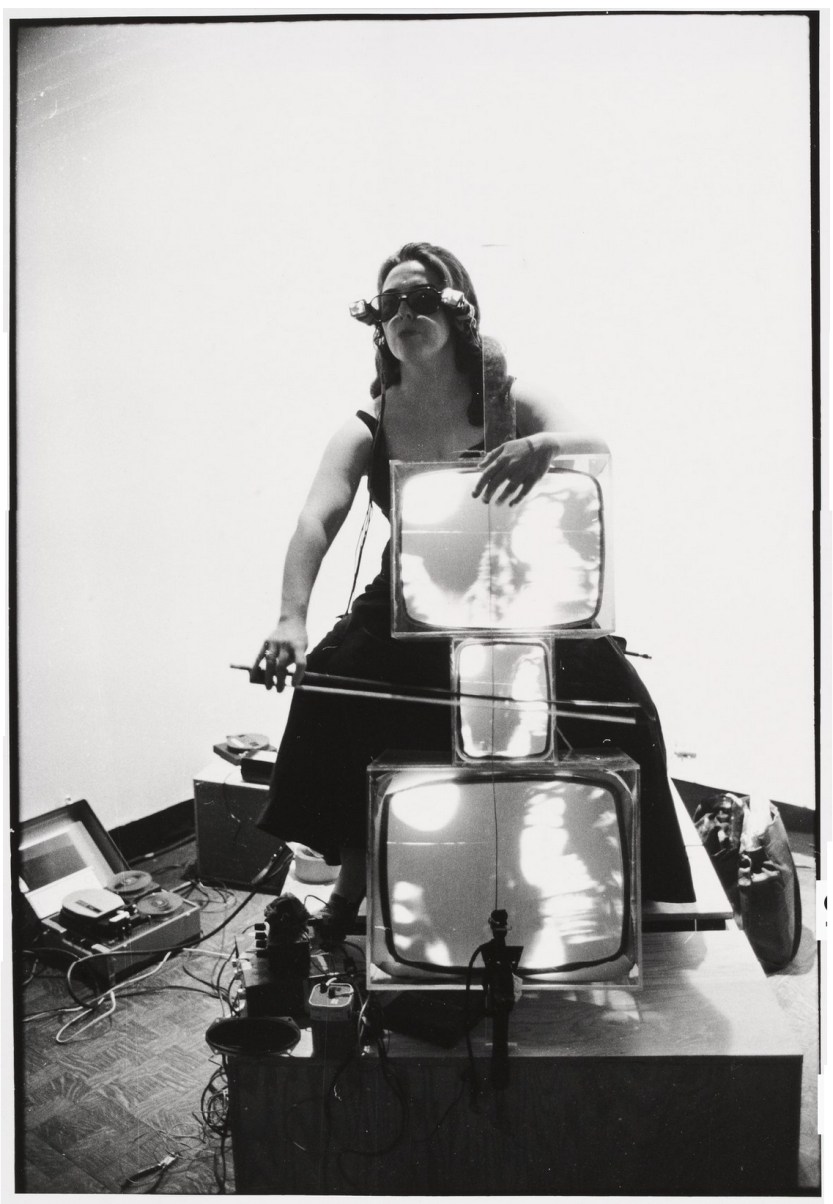

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman Performing Nam June Paik’s Concerto For TV Cello and Videotapes (1971)

Fluxus, founded by George Maciunas and springing from the creative ferment of New York in the late 1950’s and early 60’s, was one of the most radical and important swellings of creative energy of the 20th century. Picking up were Dada left off, it was an attack on the establishment – a rejection of bourgeois values, endemic within the arts. Doing away with divisionist thinking and hierarchy, it combined all of the disciples of creative practice – visual art, film, literature, music, sound, and the theatrical, into a single force. Through the multiple, it attempted to undermine capitalism – opening access, and placing complex creative ideas in the hands of all. Embracing the happening and performance, it presented an alternative to a standard of exclusivities, temporalities, and efforts of historicization, almost always applied to artworks. The movement flung open the doors, inviting everyone to participate and exist in the moment. As a gesture – following Abstract Expressionism and predating Pop, it solidified the transition toward America’s dominance as a global intellectual center. For all the good Fluxus did – leaving a towering canon of remarkable and revolutionary works in its wake, the movement’s legacy has been hobbled by paradox. It wasn’t intended to last. It was conceived as a social intervention – an activation of change – a new way of thinking and allowing art to exist in our lives, rather than a collection of artifacts to be housed in museums.

Charlotte Moorman Performing Nam June Paik’s Concerto For TV Cello and Videotapes (1971 / 1976)

Because of the politics and temporalities within which their works were conceived, few members of Fluxus sought to protect their legacies during the years of the movement’s greatest activity. To do so would have been counter to its principle ideas. As a result, as attention on it grew, its history became increasingly susceptible to influence and agenda. Much of what we know has been assembled and structured in retrospect – the results marked by strong personalities, agendas, and infighting. When speaking to those who were there, you rarely hear the same thing twice. What we know of Fluxus’ history, has been willfully modified from within and without – actions which have polarized members (and their legacies) – often favoring more famous contributors and associates, shuffling dates (who did what first), and downplaying or omitting many important efforts. As the movement has entered institutional care (historians, academics, museums, etc) its arbiters have increasingly followed this lead. The art world champions the names of Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and John Cage, while the presence of George Brecht, Henry Flynt, Tony Conrad, La Monte Young, Jonas Mekas, Yoshi Wada, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Peter Moore, Ben Patterson, and countless others including Maciunas himself, are fleeting at best.

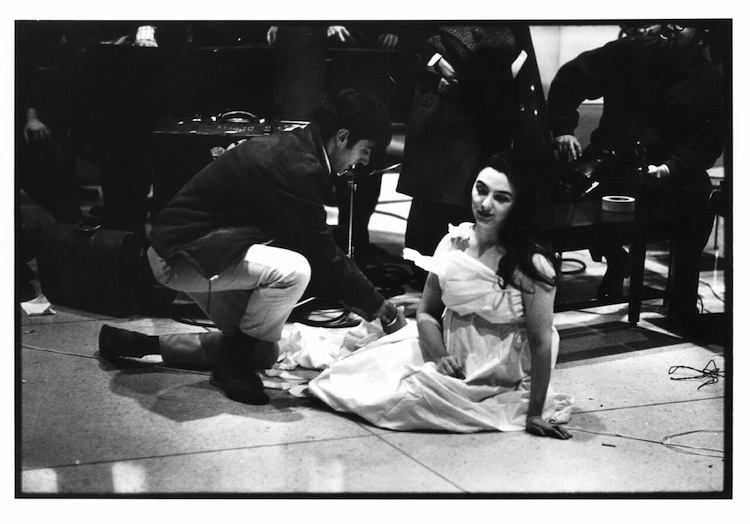

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik perform Human Cello variation as part of John Cage’s 26’1.1499″ for a String Player at Café au Go Go, New York City, October 4, 1965

As the decades passed – particularity those following her untimely death, the legacy of Charlotte Moorman has suffered far worse neglect than most members of her circle. Given how vibrant and fascinating a figure she was, with how famous she was during the movement’s heyday, it seems unlikely that this was entirely by accident. Some of it comes down to bad timing and circumstances. Moorman died during a period when Fluxus was still seen as threatening to institutional and historical agenda, and thus was willfully neglected. The importance of many of its participants has long been downplayed within the canonical authorship of its history. It wasn’t until the late 90’s and early 2000’s that the movement began to be approached more willingly, at which point Moorman (like many of its prominent figures) was already gone. Her conservative family was staunchly critical of her avant-garde gestures, she had no children, and her husband died shortly after she did. Beyond a handful of friends – most of whom lingered in the shadows with her, there has been almost no one to protect her legacy and usher it back into view.

German newsreel from 1965 – Action Music in Berlin, featuring Moorman.

Though Fluxus presented a far better vision of gender equity than most creative movements of its era, the fact that Moorman was a women can not be stepped over. By all accounts, she should be a feminist icon. She is not. Some of this is a byproduct of her role, rather than an explicit consequence of gender discrimination. She was a collaborator and collectivist. She worked the help realize the efforts of others, and thought very little of herself – seeing herself as a participant within a larger effort within which individualism should be dissolved. Nearly everyone who knew her, described her as the most selfless person they had ever met. It was not in her character to champion the importance of her actions. Moorman considered herself part of the grand tradition of Classical musicians – individuals who sublimated the self, in service of a composer’s work. This is logical given her background and training, but fails to acknowledge the character of her contributions within the context within which she worked – the collectivist spirit which brought it to be. When a work was conceived for her, fully realized by her, and entirely dependent on her actions and interpretations, it is no longer solely the composer’s work. It is a collaboration – as much hers as theirs. Moorman was a victim of her optimism. In order for the things she believed in to work, all parties must agree.

Howard Weinberg / Nam June Paik – Topless Cellist, Charlotte Moorman (Documentary)

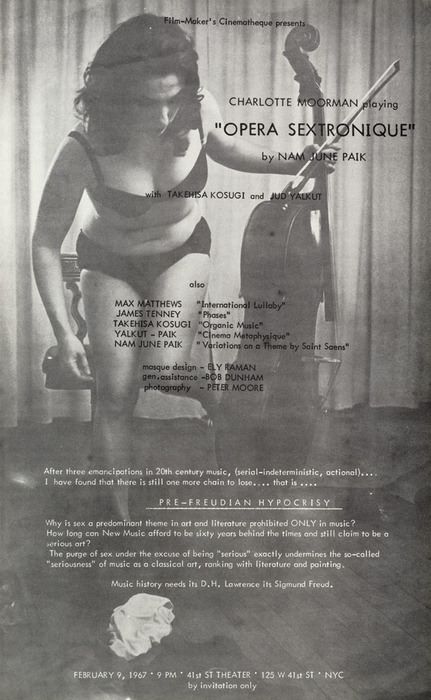

There is little question that singularity and importance of Moorman’s contributions to collaborative efforts have been downplayed. You can’t ignore the fact that she worked almost entirely with men, many of whom are now incredibly famous – in some cases stemming from the attention received by works she contributed to. Yet her name has been pushed from view. It’s impossible to completely know if there was a schism between how they conceptualized her involvement and her own. My guess is that she was often used – a vehicle for the career of another. Particularly after 1967, when she was tried and convicted for obscenity after performing a Nam June Paik work topless, she would have brought notoriety and credibility to almost any performance. Being who she was, she was happy to help, but it doesn’t excuse those who failed to offer her the credit she deserved – be those the artists themselves, or those who have promoted their legacies. Her talent, vision, and contributions made these works what they were. Everyone knew this at the time. Even if discounting the fact that these works were composed for her, and thus would not have otherwise existed, had another cellist taken her place, they could have never been what they became.

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman in a performance of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece at New York University (1967)

Moorman’s presence within the narrative is inconvenient. Her actions display the selfless collectivism from which Fluxus grew. As external and internal perception of the movement changed over the decades – increasing paying homage to totemic individualism, her participation was recast. In order to sustain the careers of those she supported – the singularity of their “genius”, her contributions and voice were suppressed – reducing to her to nameless women – a performer wielded men. This is not what she was. When observed through an honest lens, her evolving presence within history holds threatening truths – a reminder that the elevation of careers – the very idea of the fame itself, stands in opposition to the basis for the movement from which many famous figures sprang. The history we now hold, is largely built from lies.

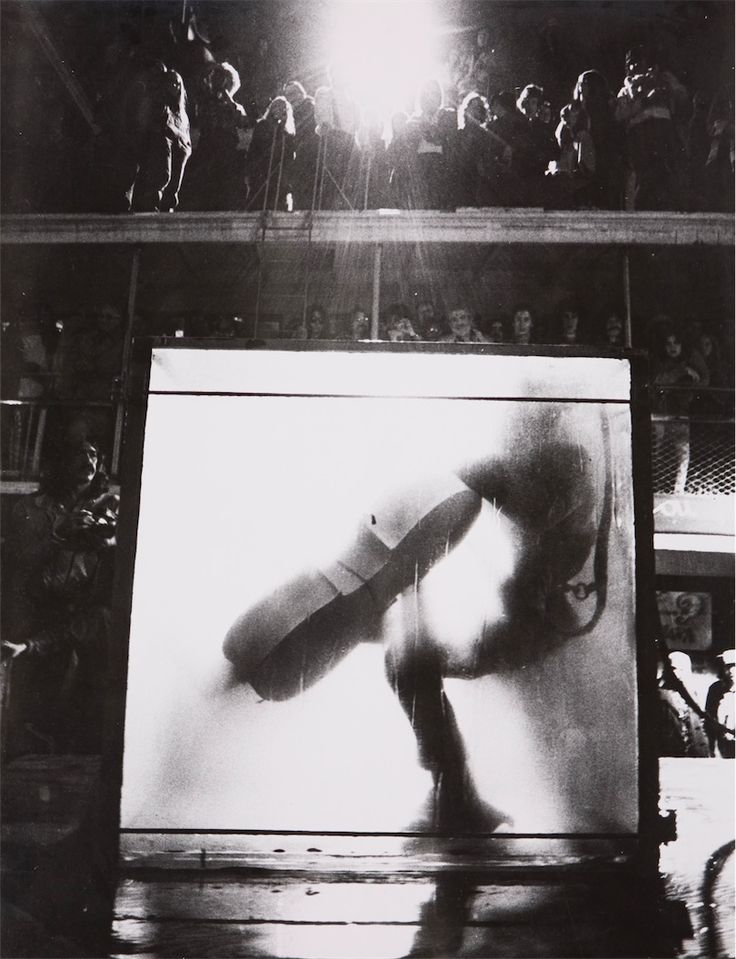

Charlotte Moorman performs Jim McWilliams’s Ice Music for Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1976. Photographer unknown.

Perhaps the saddest truth hanging over Moorman’s legacy is how she was regarded by other women. A selfless pioneer in every action, she is almost entirely absent from the feminist narrative – the very movement which should have protected her. Surprisingly, despite the profound positive effect she had, most prominent feminist voices of her era – members of the second wave of feminist thought, despised her. Moorman was a strong woman who proudly displayed her body as she saw fit – nude, in costume, a component in a work of art, or simply in a ball gown – entirely in control, while attempting to operate with equity in a world of men. She stood in opposition to theoretical zeitgeist of her day – an inconvenient proof beyond binary thinking – of another way. Fascinatingly, Moorman’s cultural position has been widely adopted by fourth wave feminists during the last decade. She suffered for being ahead of her time. Due to the neglect she continues to endure, she remains a pioneer that contemporary feminism doesn’t know it had.

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman performs Jim McWilliams’s The Intravenous Feeding of Charlotte Moorman, 9th Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York (1972)

Moorman was an artist of profound historical importance – crossing context and creative field. She is unquestionably one of the most important voices of the 20th century, yet suffers an unjustifiable neglect. The state of her legacy – as an artist, a musician, and as a women, are windows into the inequities which lay behind the authoring of institutional histories. Her work offers important capsules of truth. They are among the purest examples of Fluxus’ original intent. The products of a staunch collectivist, playing a decisive but under-appreciated role – an active participant who dedicated most of her efforts to supporting and facilitating the work of others. Sadly, the neglect that Moorman continues to endure does end within the narratives of 20th century fine art or the struggle for gender equity. Perhaps her greatest contribution remains almost entirely unknown. In the face of the towering legends of the composer with whom she worked and supported, her incredible work as a facilitator of avant-garde music – of those who made the sounds she loved, has been almost completely lost.

Poster for performance of Nam June Paik’s Opera Sextronique

A few years ago, while I was still living in NY, I met a woman named Barbara Moore. Barbara is the widow of Peter Moore – a member of Fluxus, and the photographer who almost single-handedly documented all of its activities in NY during its many years. If you have seen a photo of Fluxus event, it was most likely taken by him. Like Moorman, Peter was a collectivist and supporter of the efforts of others. Similarly, his legacy has suffered omission and neglect. It is largely through his images that we has as much information about Fluxus as we do. More than any other figure, he allowed the movement to pass the tests of time. Everyone involved owes him a profound debt – as do we all, but few wanted to offer him the credit he deserved for the singular creativity of his eye. The simple, and seemingly obvious act of having his name credited to the images he took, has been a battle Barbara has fighting relentlessly since his death.

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik, TV Bra (1969)

As Barbara and my friendship grew, she began to tell me first hand accounts of the inner workings of Fluxus, and details of nearly every major happening and performance that movement guided into existence. She had been there for it all. The longer she spoke, the more I began to consider the inequities of history. While many figures like her husband have been unfairly neglected, there were always others lingering even further from view – those whose efforts were of equal importance, while their names were rarely known beyond intimate circles. Their actions were ephemeral – leaving ripples in their wake, rather than artworks. Barbara was not only a supporter of Fluxus, she became its archivist. While Peter had photographed, she was at his side, making notes and collecting every artifact she could. What she assembled now accounts for the astounding Fluxus collection at Harvard’s Fog museum – one of the largest in the world. She was also the first person Dick Higgins hired when he founded the seminal Something Else Press. In her role, she helped sculpt one of the greatest bodies of avant-garde publishing of the 20th century.

Charlotte Moorman performing with Joseph Bueys

The tales went on. My eyes and ears brimmed with envy. Knowing of my love of avant-garde music, Barbara eventually began to pull photos taken by Peter that no one had ever seen – accompanied by statements like “I think this was Terry’s first performance of In C” and “here’s another one of La Monte.” As my enthusiasm and curiosity grew, she began to focus my attention toward images and tales from The Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York, run by one one of her closest friends – Charlotte Moorman. A world began to unfold.

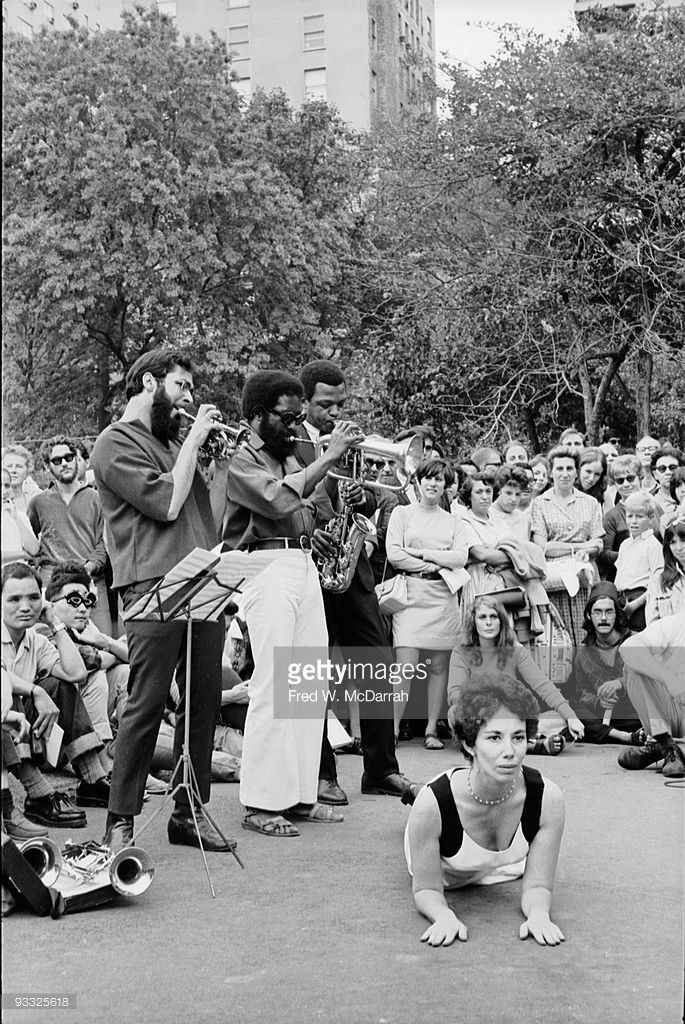

Fred W. McDarrah – Dew Horse, a performance with dance by Judith Dunn and music by Bill Dixon – 4th Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York (1966)

Though I had read references to The Avant-Garde Festival in the past, I knew almost nothing about it. I had no idea that it was conceived and run by Moorman, and had assumed that it was largely focused on Fluxus music. When Barbara mentioned the festival had been where she had first seen San Ra, I knew that I had missed something profound. For that mater, so had most of the contemporary experiential and avant-garde music worlds. A significant part of our history had been lost.

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman performs Jim McWilliams’s Sky Kiss, 6th

Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York (1968)

Those of us who are part of contemporary iterations of the experimental and avant-garde music community, rarely address how divided our history has been. Many of us have come to embrace a vast field of organized sound – approaching it with equity, but this is not how it always was. You only need to look as far as John Cage’s attacks on other composers and forms of music, to see the division and imposition of hierarchy laying at our core. It took many years to lay to this to rest – to arrive where we have, and there is still plenty of work to be done. If there is one thing I have learned since entering a more public role by writing The Hum, it is how much elitism, judgement, and snobbery still lingers below the surface of this sonic world. Charlotte Moorman saw beyond this more than half a century ago. The Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York, which she organized and ran between 1963 and 1980, was profound political statement far ahead of its time – drawing nearly every thread of avant-garde music – from Free-Jazz, to art music, and countless conflicting philosophies of avant-garde classical music, into a single fold. The festival stood against odds – an attempt to support the many musics she believed in and loved. She offered them voice – giving forum – attempting to inspire conversation between them and break down endemic barriers and division. As I learned more about Moorman and her festival through the words of her dear friend (Barbara was asked to be an executor of her estate when she died), her efforts – the spirit and and philosophies from which they grew, began to lay the foundation for the gesture which now takes up most of my time. Moorman’s life, work, and festival, grew from a dualism of faith. Her work did not end with her support of the work and artists she loved. Her belief in this music was so deep, that The Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York was founded with new and potential audiences in mind.

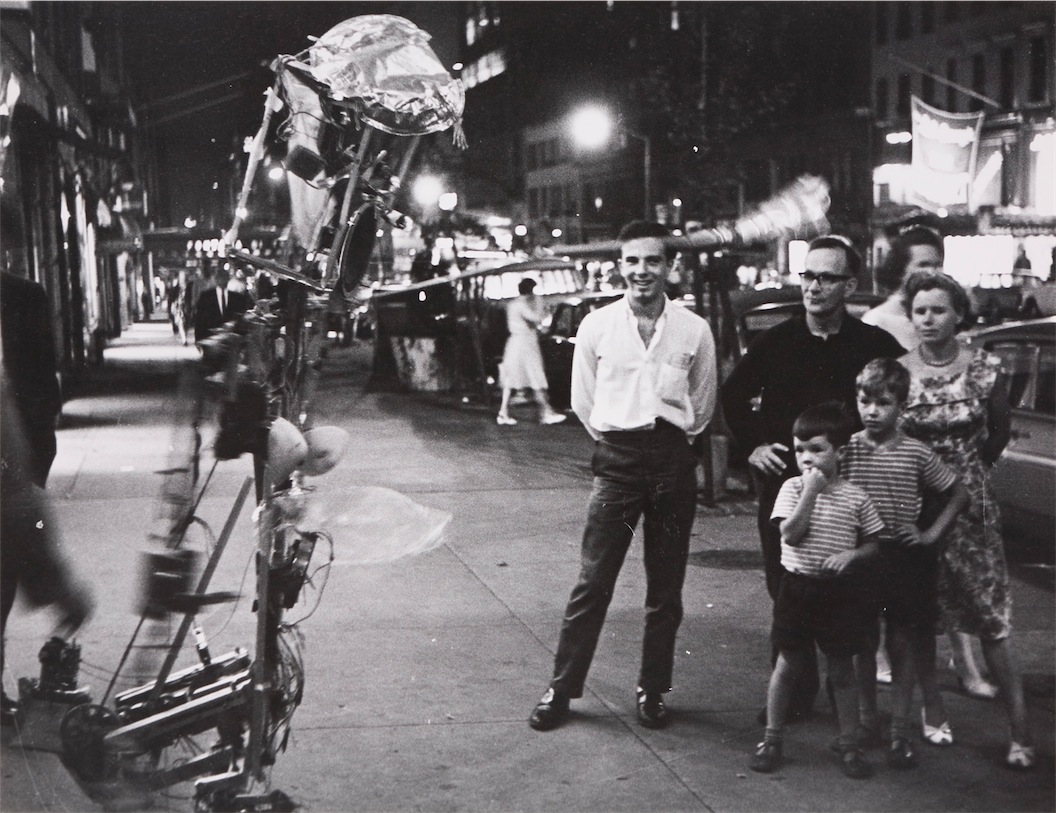

Peter Moore – Paik’s Robot Opera, II Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York (1964)

Over the course of her life, Moorman struggled to understand why the musics she loved were not embraced by broad audiences. She believed that they were for everyone, and that everyone was capable of understanding and appreciating them. As a public figure, she became avant-garde music’s great champion. This theme runs through almost every interview and television appearance she gave – absorbing the ire and laughter – challenging people to approach these remarkable organizations of sound. Her festival was a conceived as vehicle to bring more people to it – to use her celebrity as an open door. It was a platform for the ears as much as sound – an effort to open access and break down the perception of elitism which surrounded the avant-garde.

Peter Moore – Charlotte Moorman performs Wolf Vostell’s Morning Glory, 4th Annual New York Avant Garde Festival, Central Park, September 9, 1966.

Charlotte Moorman’s Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York, is one of the most important gestures in the history of 20th century music, and more so within the discrete narratives of the experimental and avant-garde. Given how ambitious it was, and how long it lasted, it’s shocking that it isn’t more well know. Rather than go into depth regarding its details – venues, line-ups / collaborations, etc, I thought it would be best to share the documents and ephemera I have been able to assemble. Within them, unfold fifteen of the most remarkable efforts of autism and sound that have ever existed. May they help keep the incredible woman at their helm in your mind, and begin to repair the sins of time. For those who are interested in exploring Moorman’s work further, you can pick up a number of her posthumously released recording here.

-Bradford Bailey

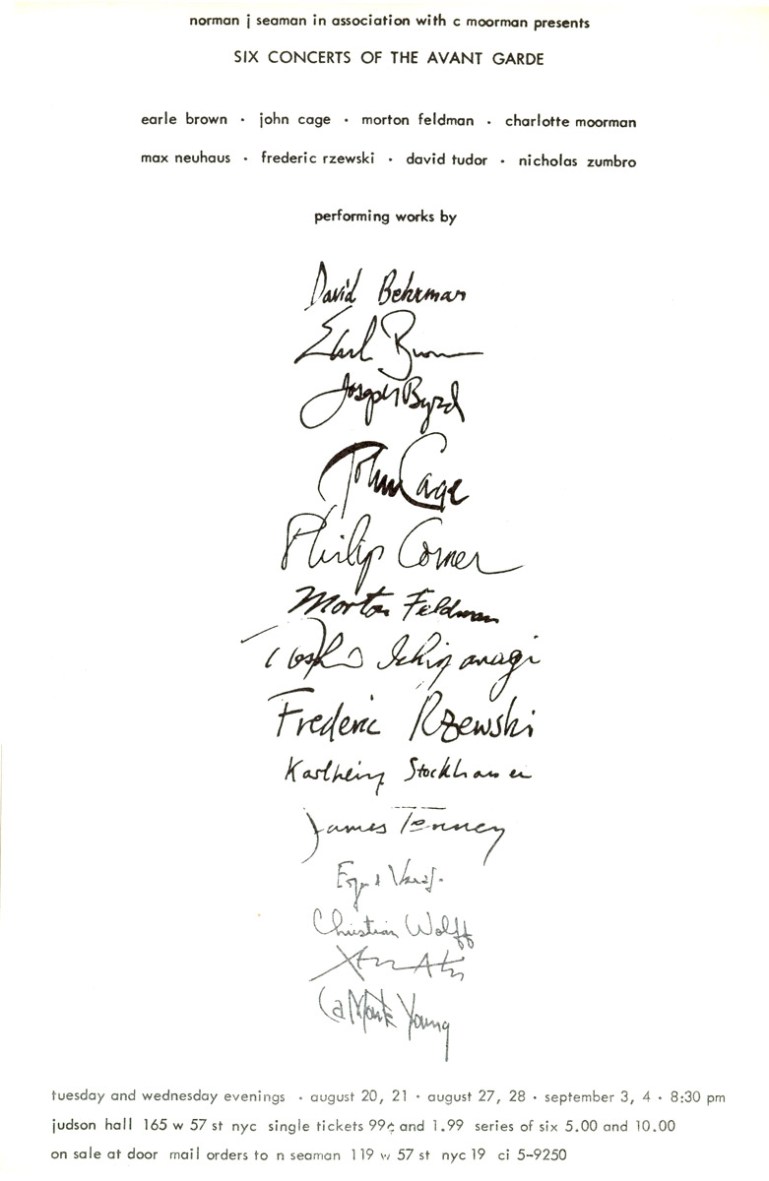

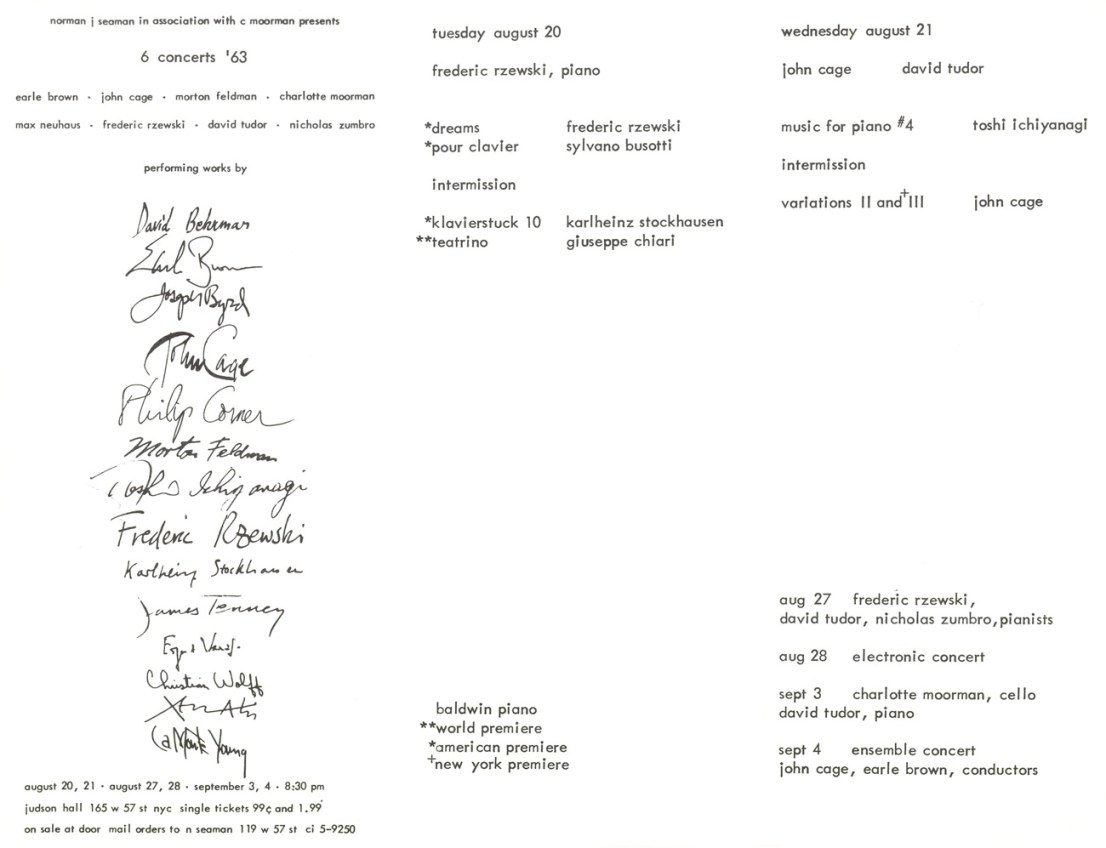

Program flyer from The 1st Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1963

Program flyer from The 1st Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1963

Program flyer from The 1st Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1963

Program flyer from The 1st Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1963

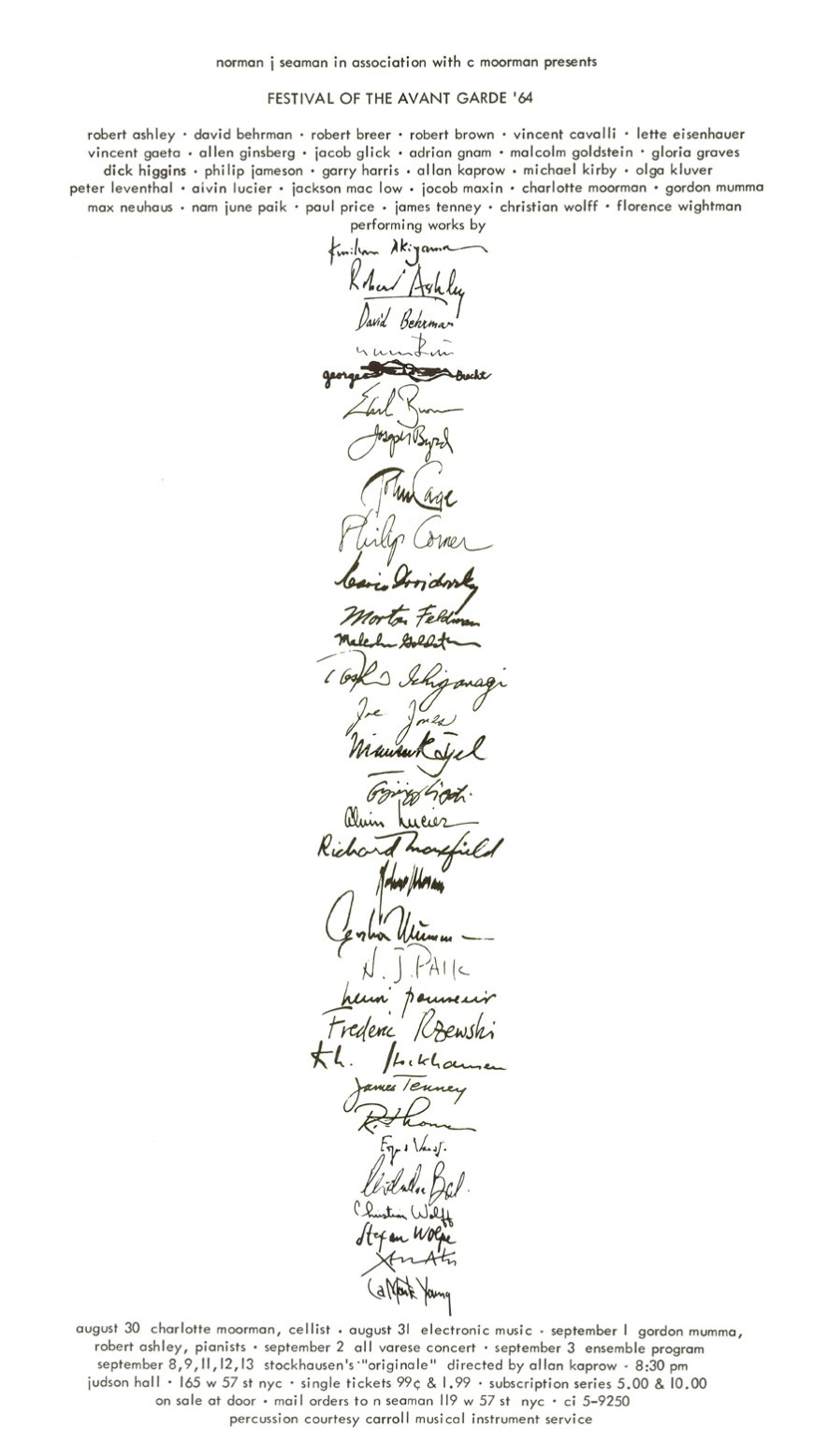

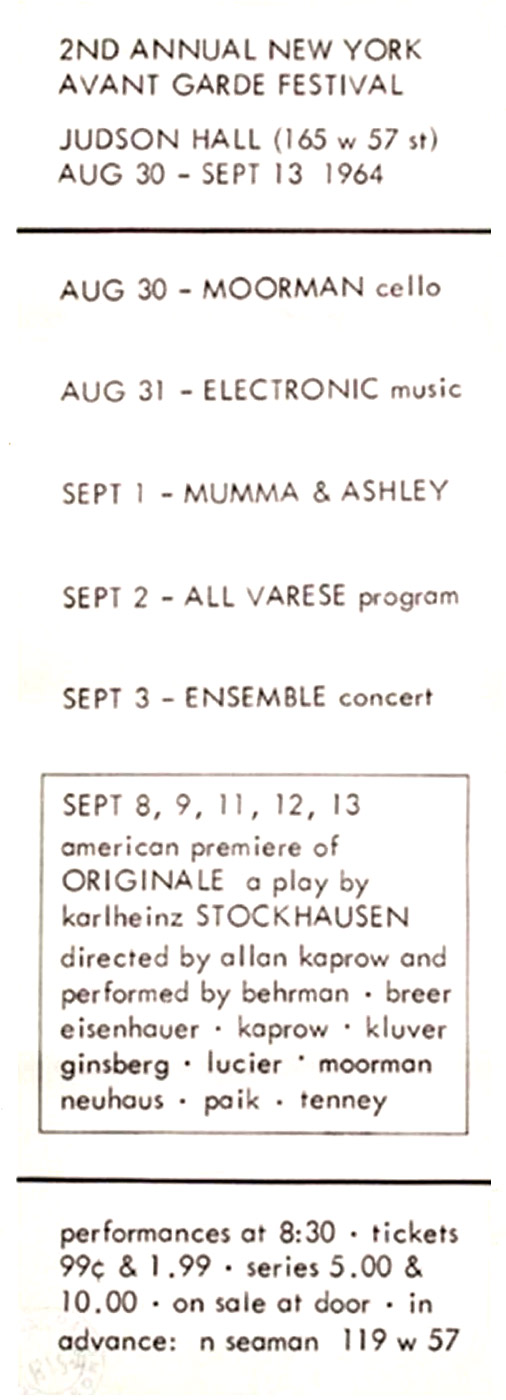

Program flyer from The 2nd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1964

Program flyer from The 2nd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1964

Program flyer from The 2nd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1964

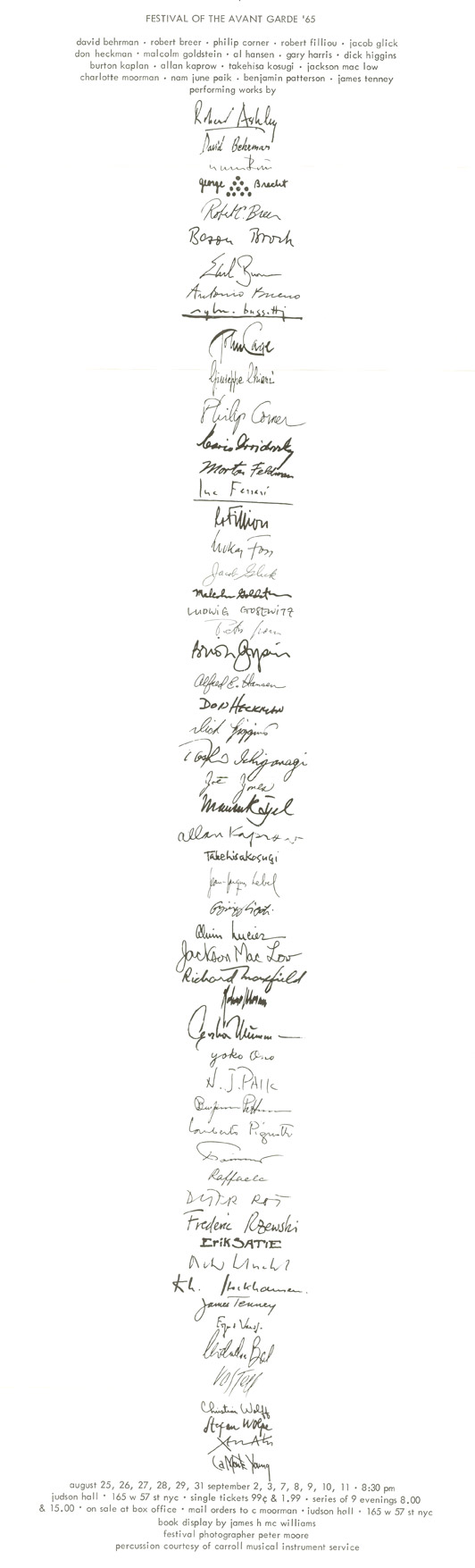

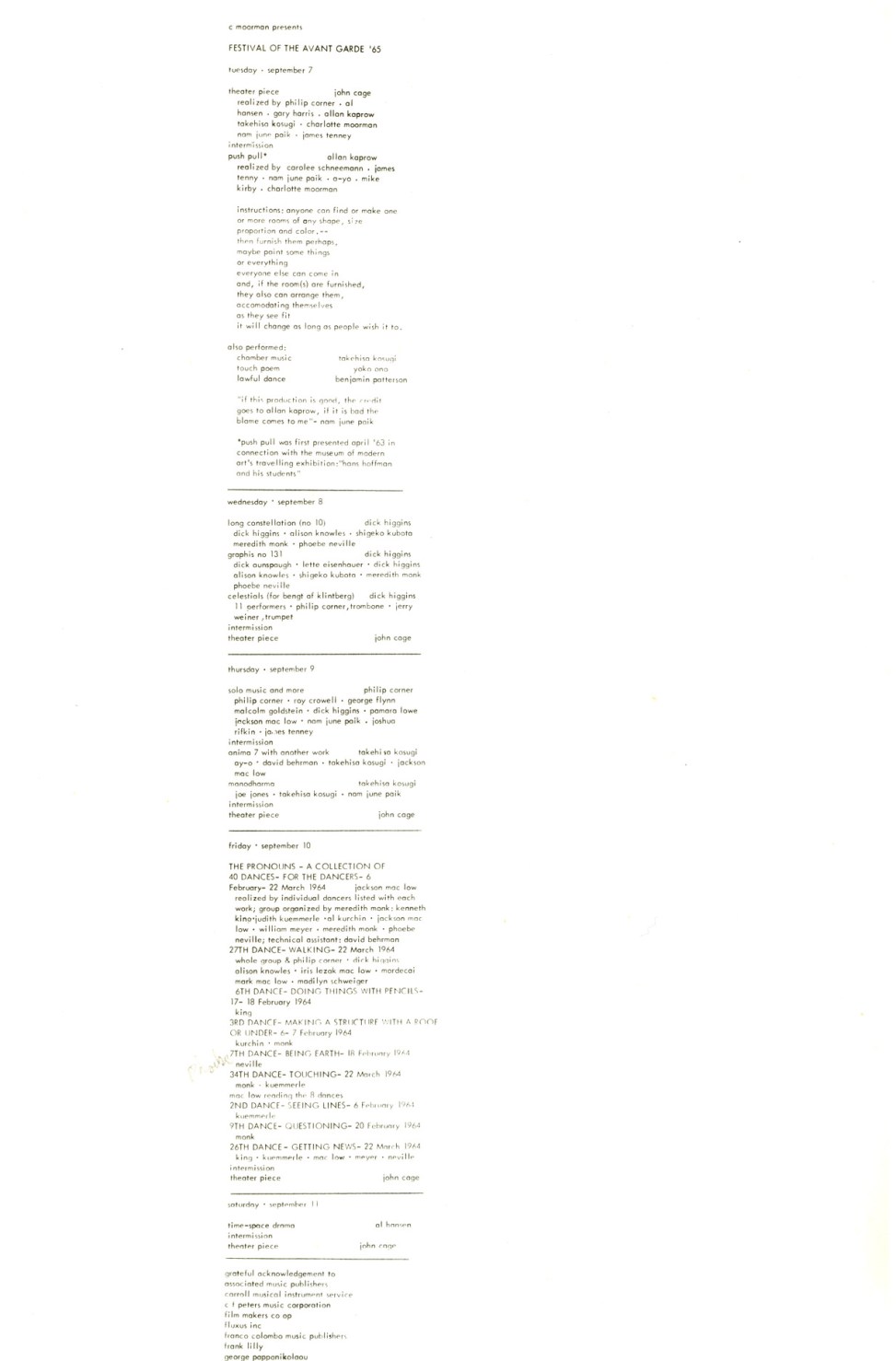

Program flyer from The 3rd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1965

Program flyer from The 3rd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1965

Program flyer from The 3rd Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1965

Program flyer from The 4th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1966

Program flyer from The 4th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1966

Program flyer from The 4th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1966

Excerpt of 4th Annual New York Avant Garde Festival by Jud Yalkut, featuring an excerpt from Morning Glory by Wolf Vostell, performed by Charlotte Moorman.

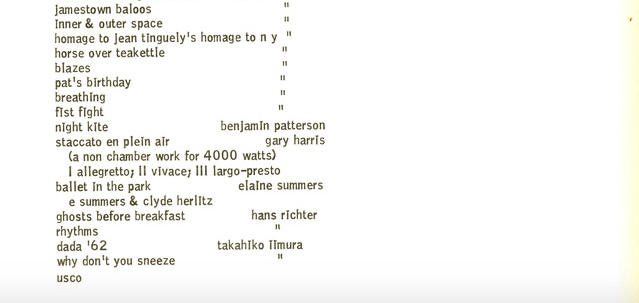

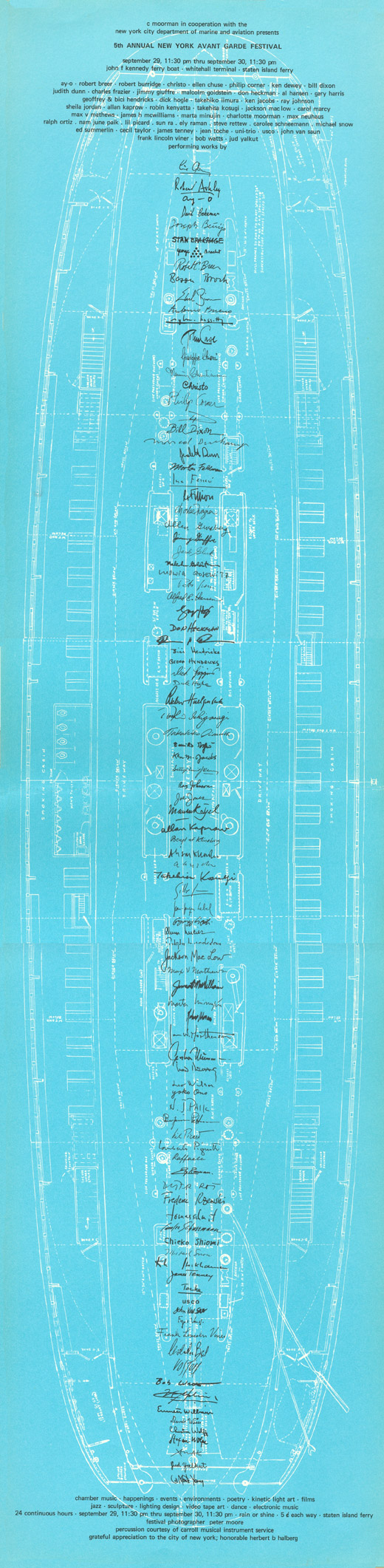

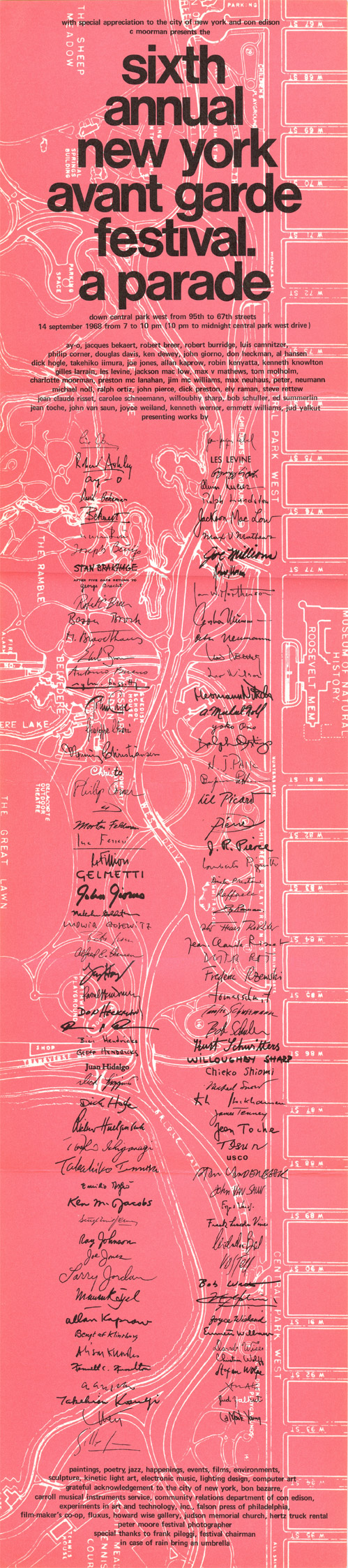

Program flyer from The 5th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1967

Program flyer from The 5th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1967

Filmed documents from The 5th Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York (1967)

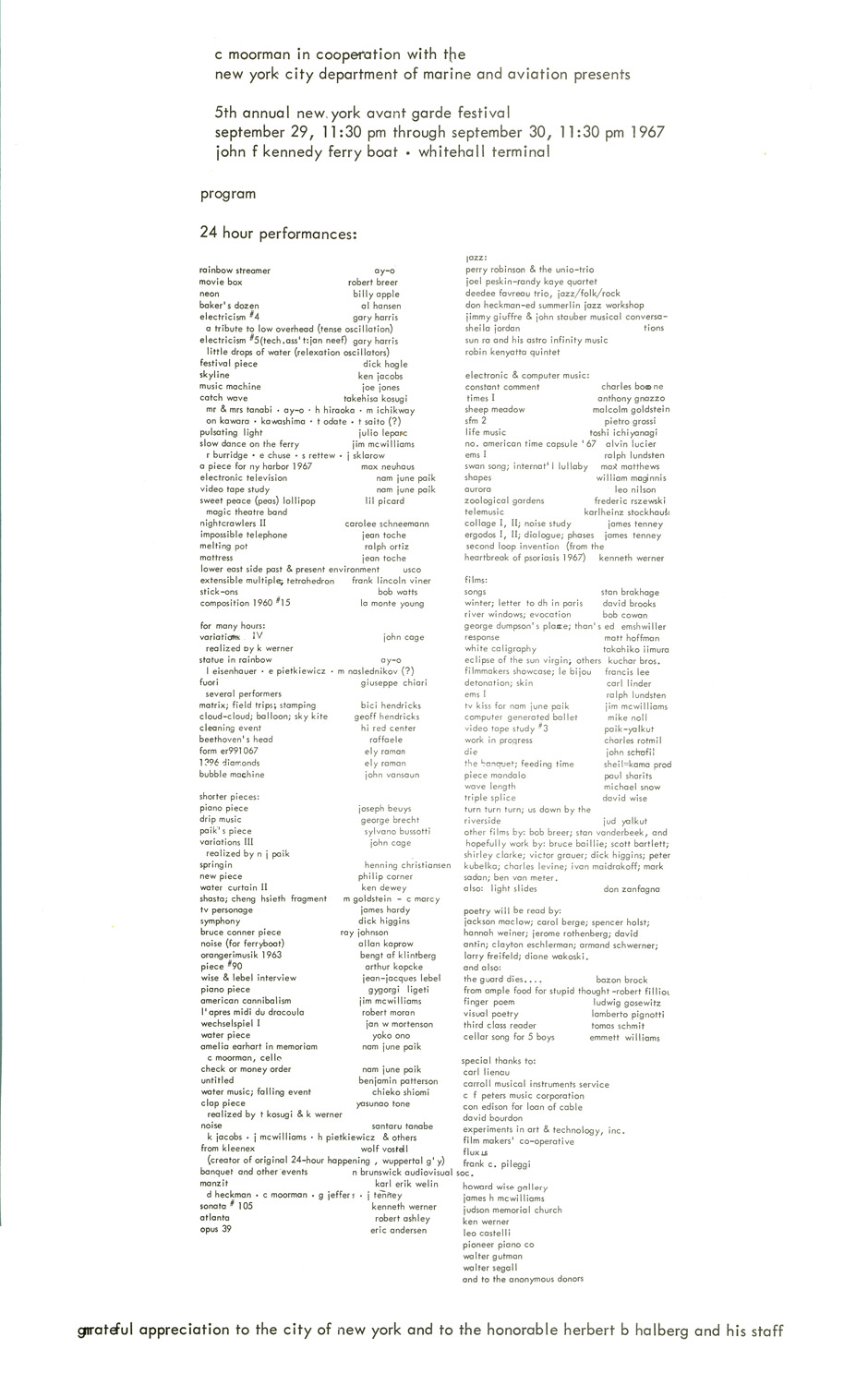

Program flyer from The 6th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1968

Press release for The 6th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1968

Press release for The 6th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1968

Introductory letter by Frank Pileggi

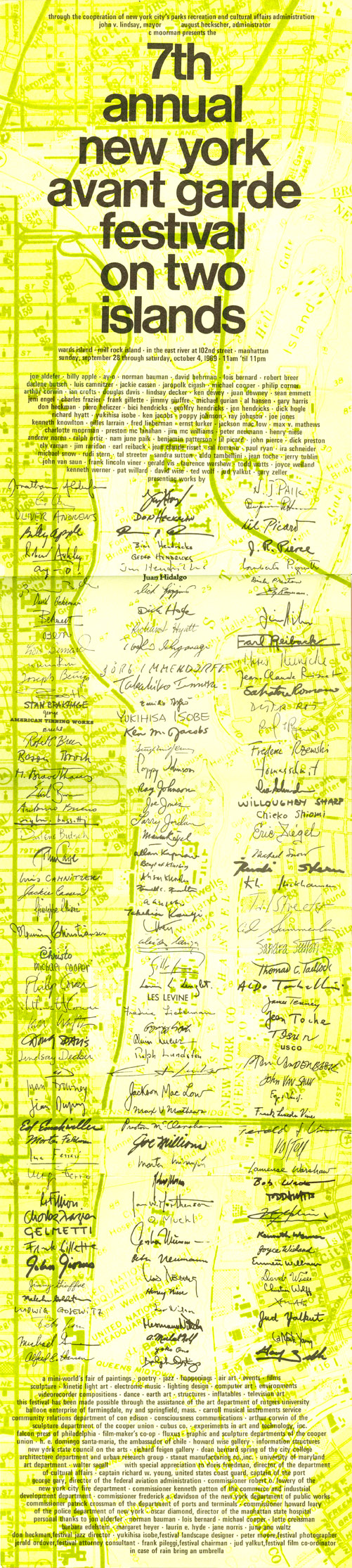

Program flyer from The 7th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1969

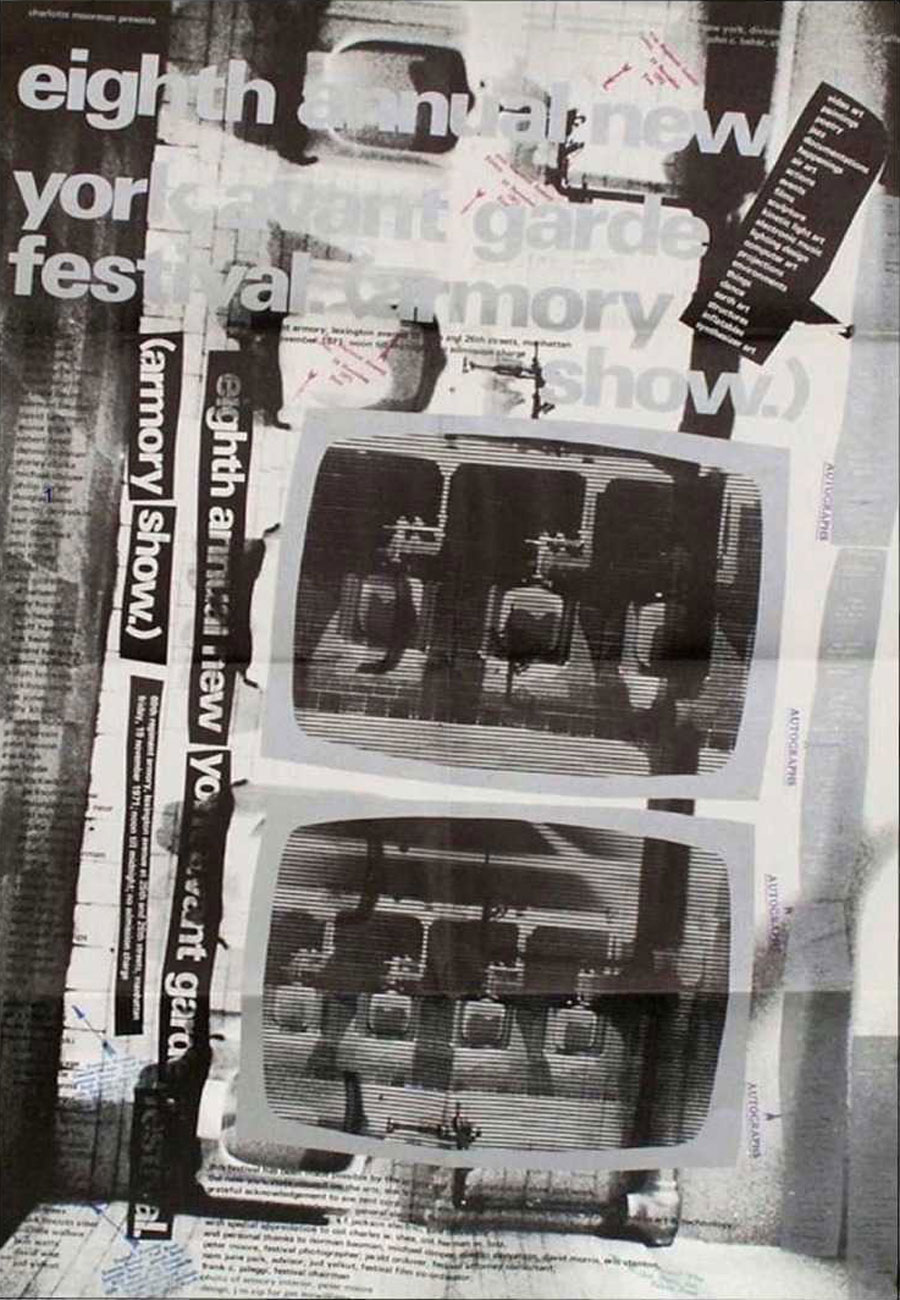

Program flyer from The 8th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1971

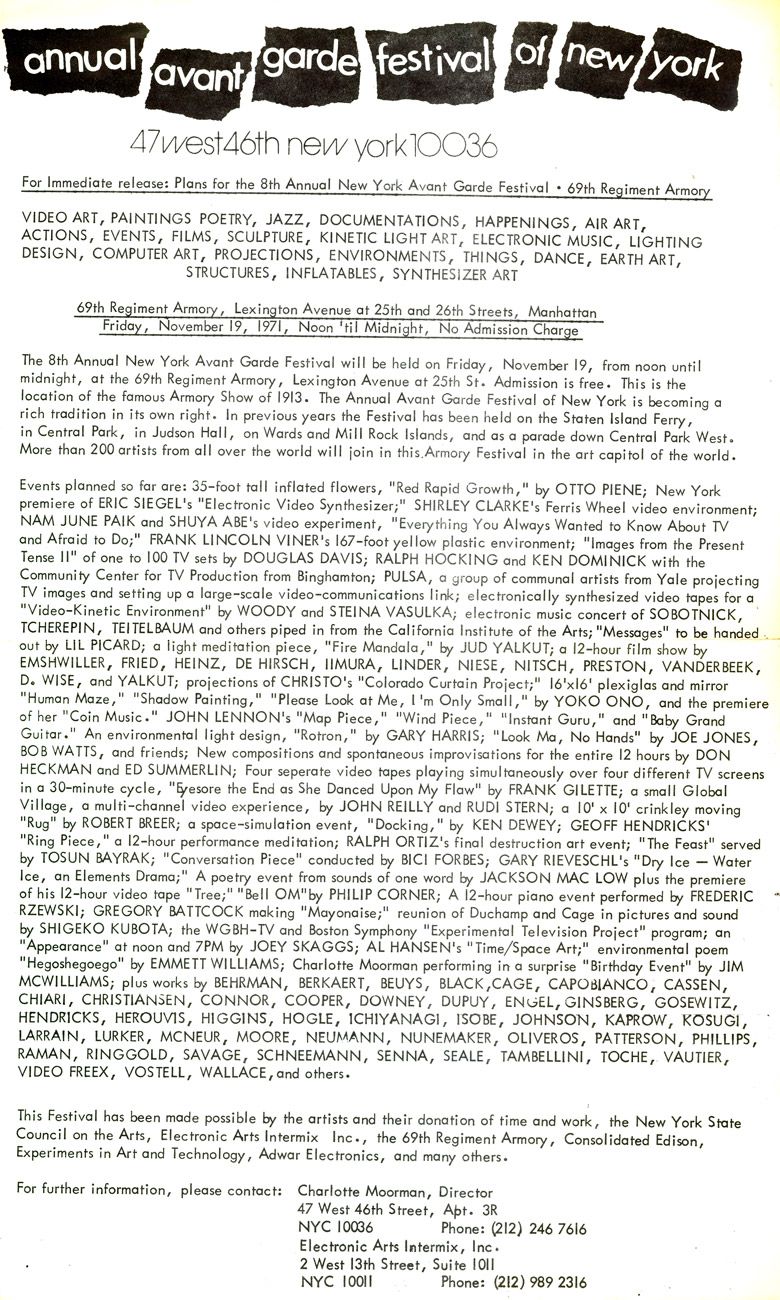

Press release from The 8th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1971

Press release from The 8th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1971

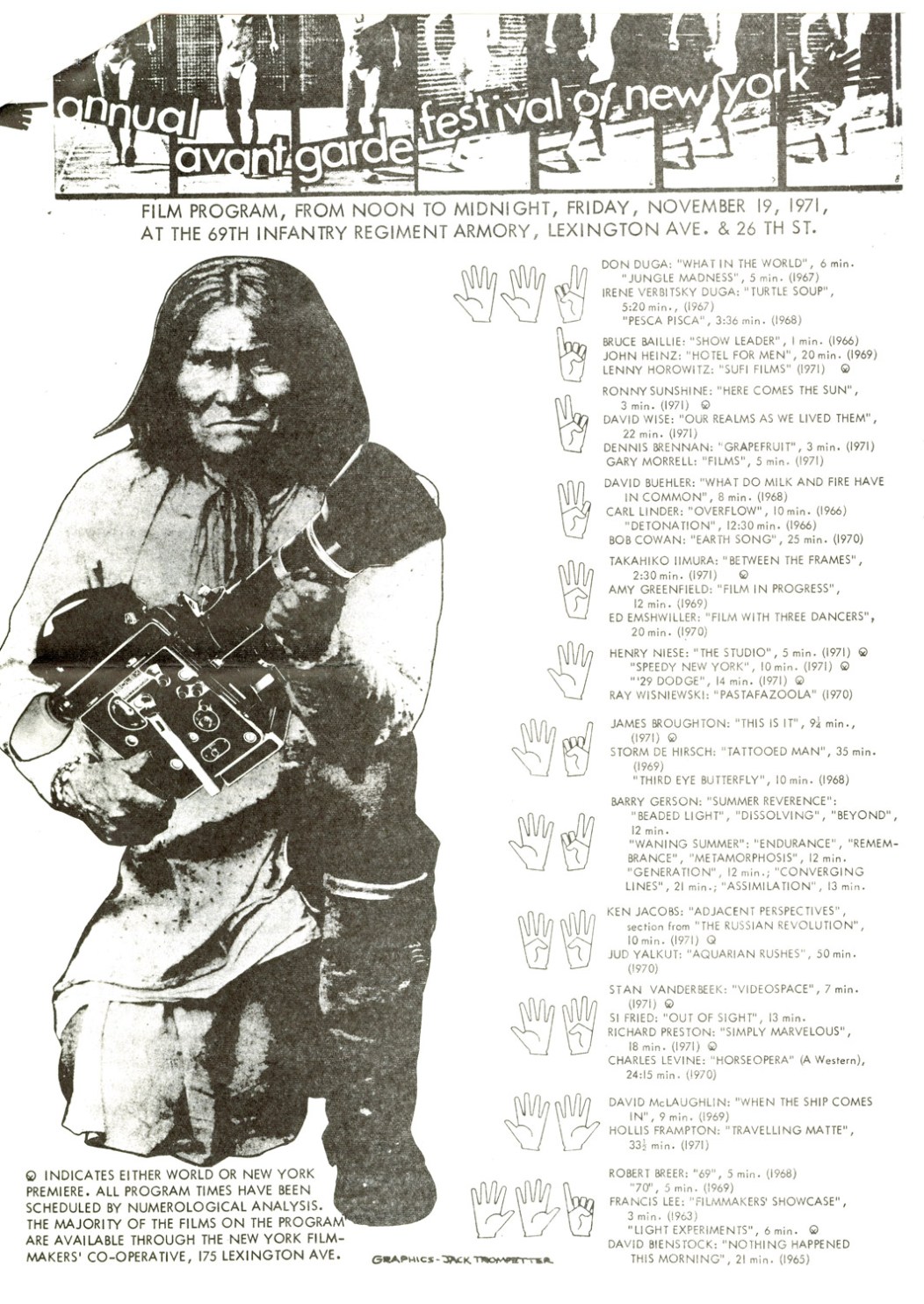

Program flyer from The 8th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1971

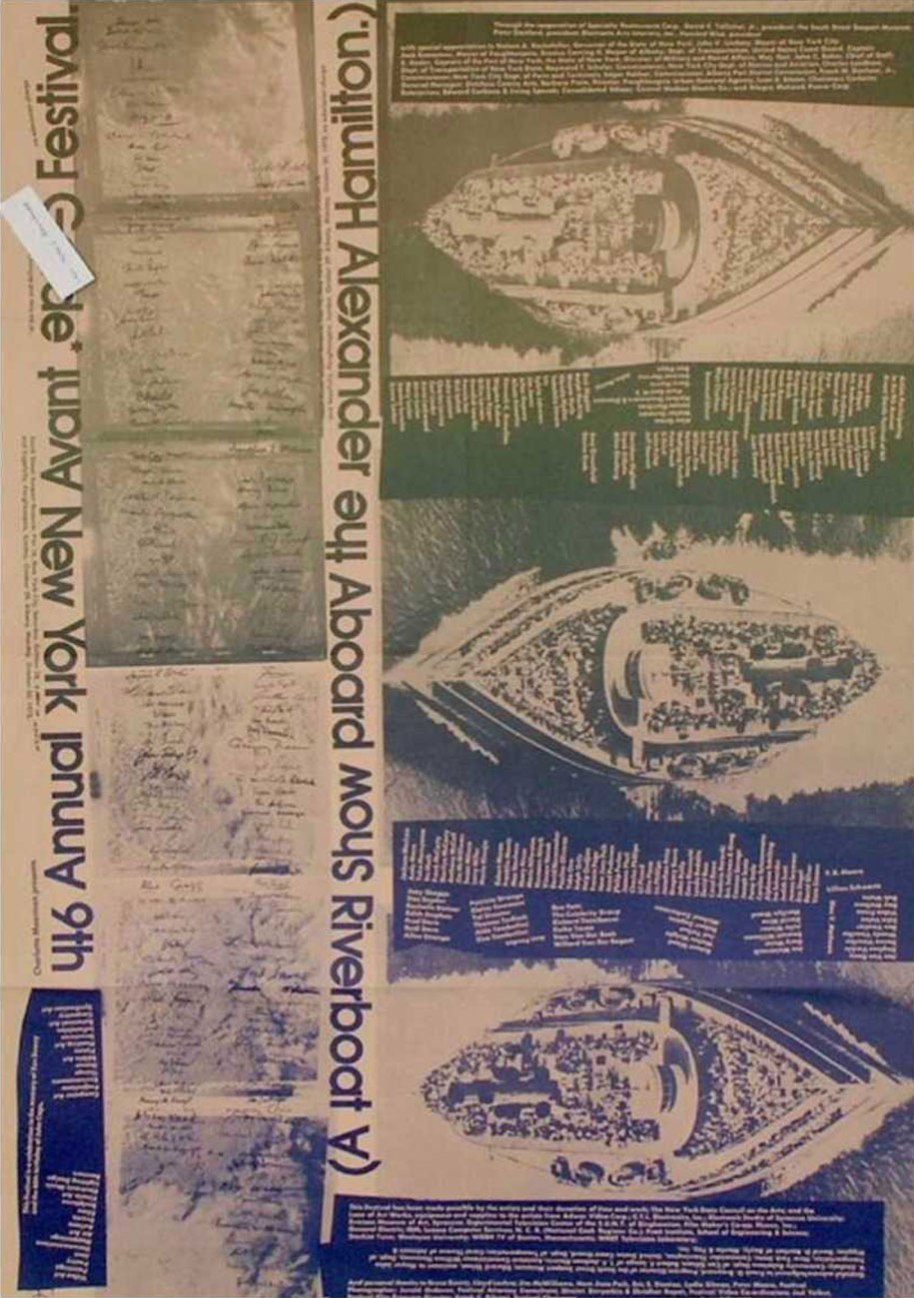

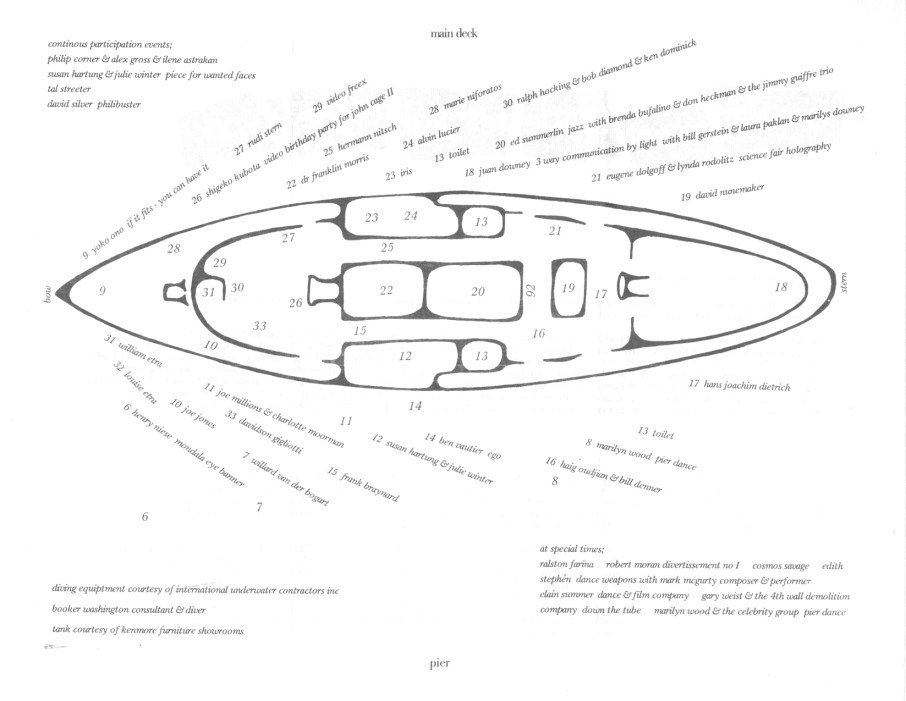

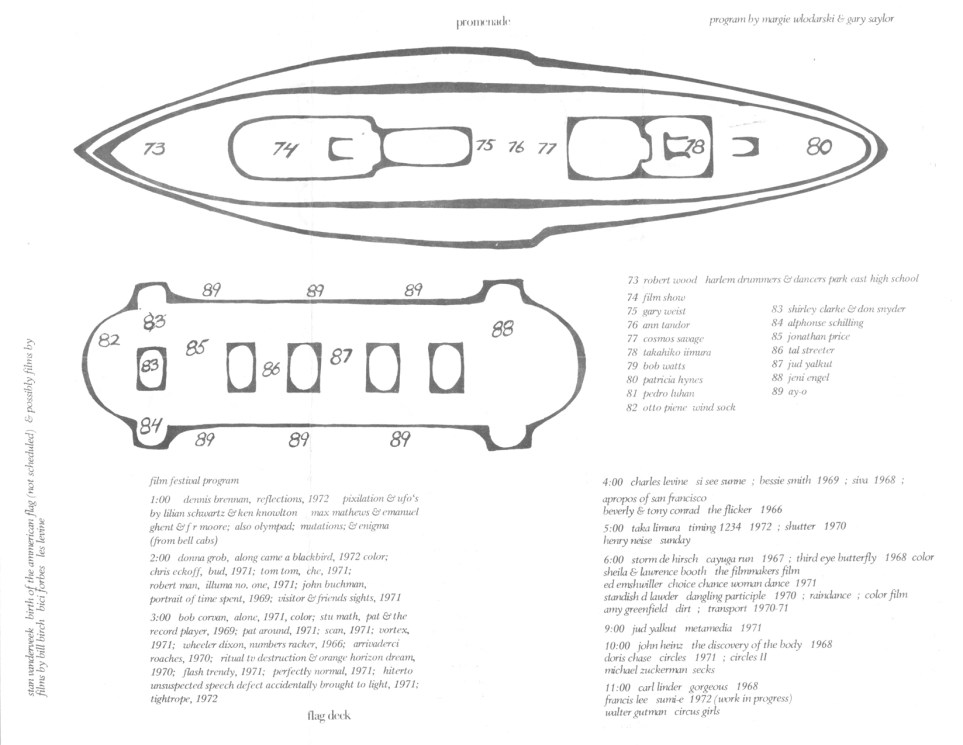

Program flyer from The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Press release from The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Press release from The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Announcement / plans for The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Announcement / plans for The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Announcement / plans for The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Announcement / plans for The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

Postcard from The 9th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1972

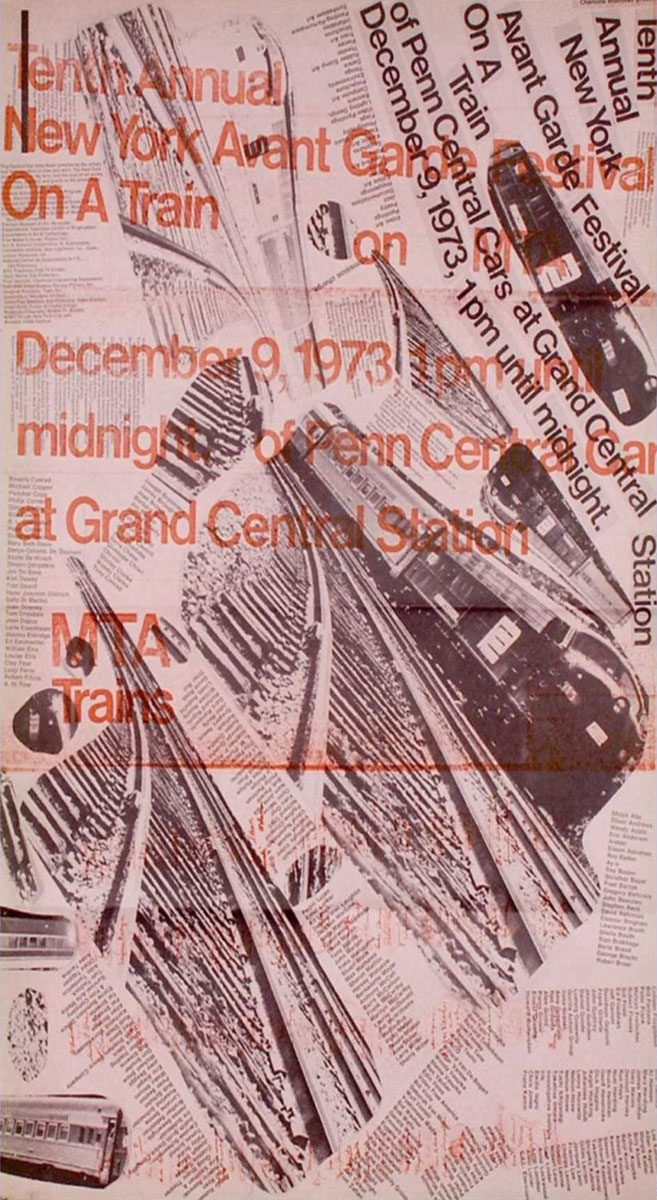

Program flyer from The 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1973

Press release for The 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1973

Artists pass from The 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1973

Announcement / plans for The 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1973

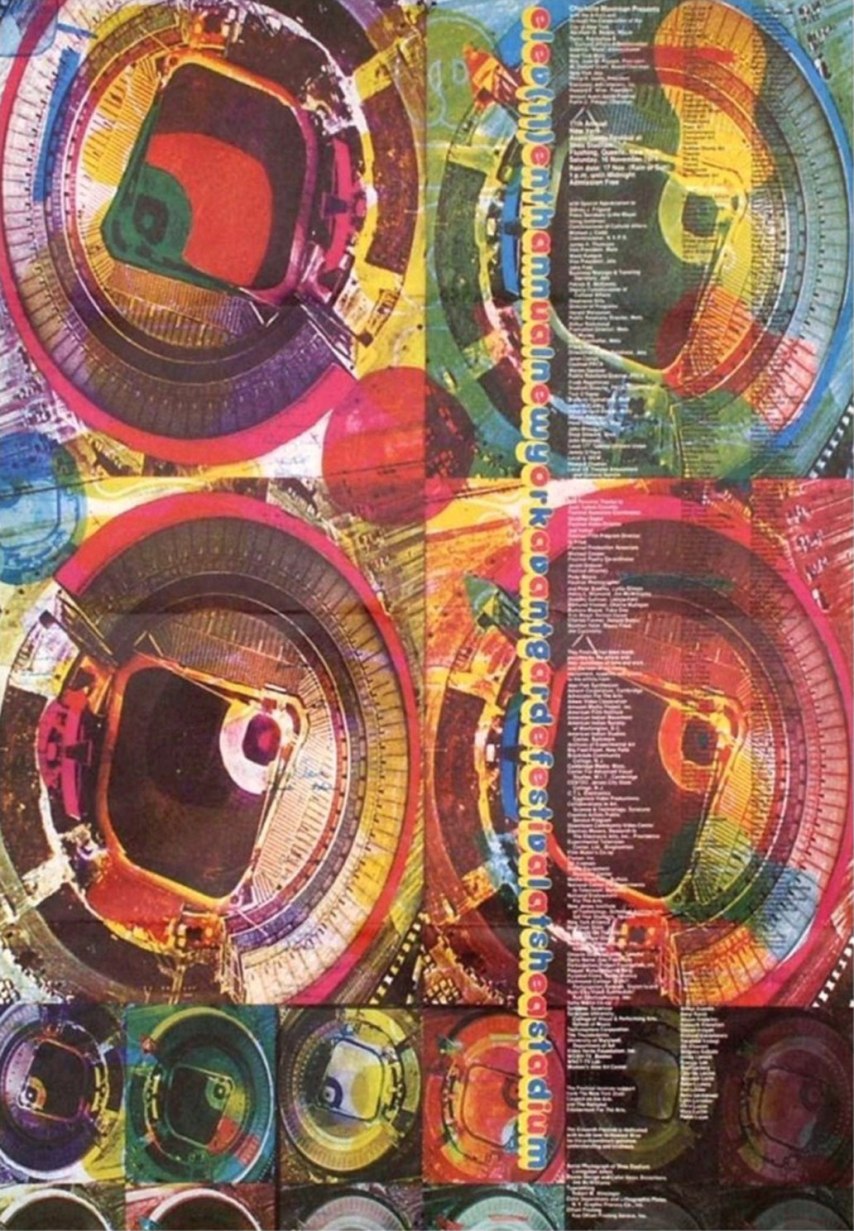

Program flyer from The 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1974

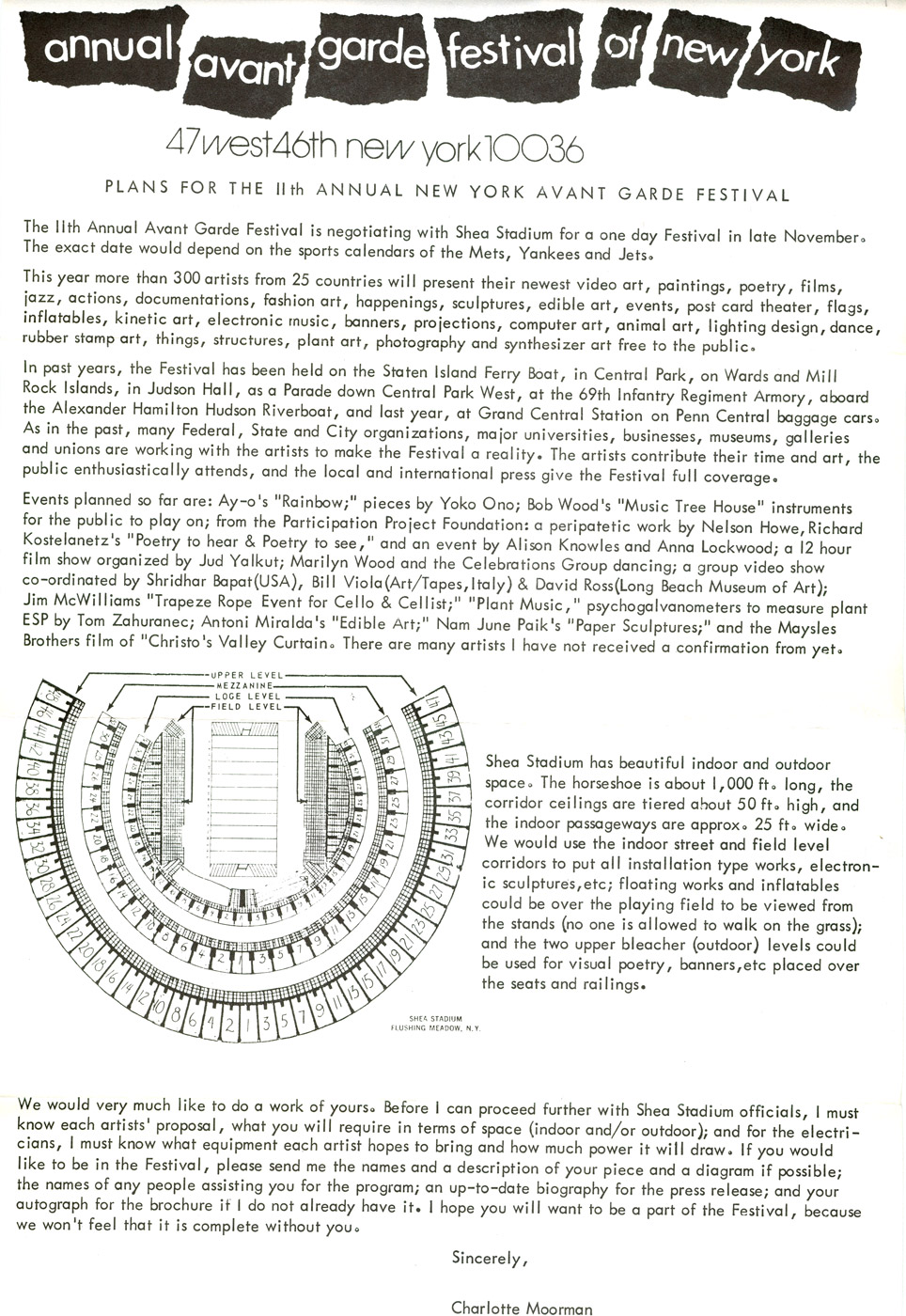

Plans / Artist invite for The 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1974

Artist information for The 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1974

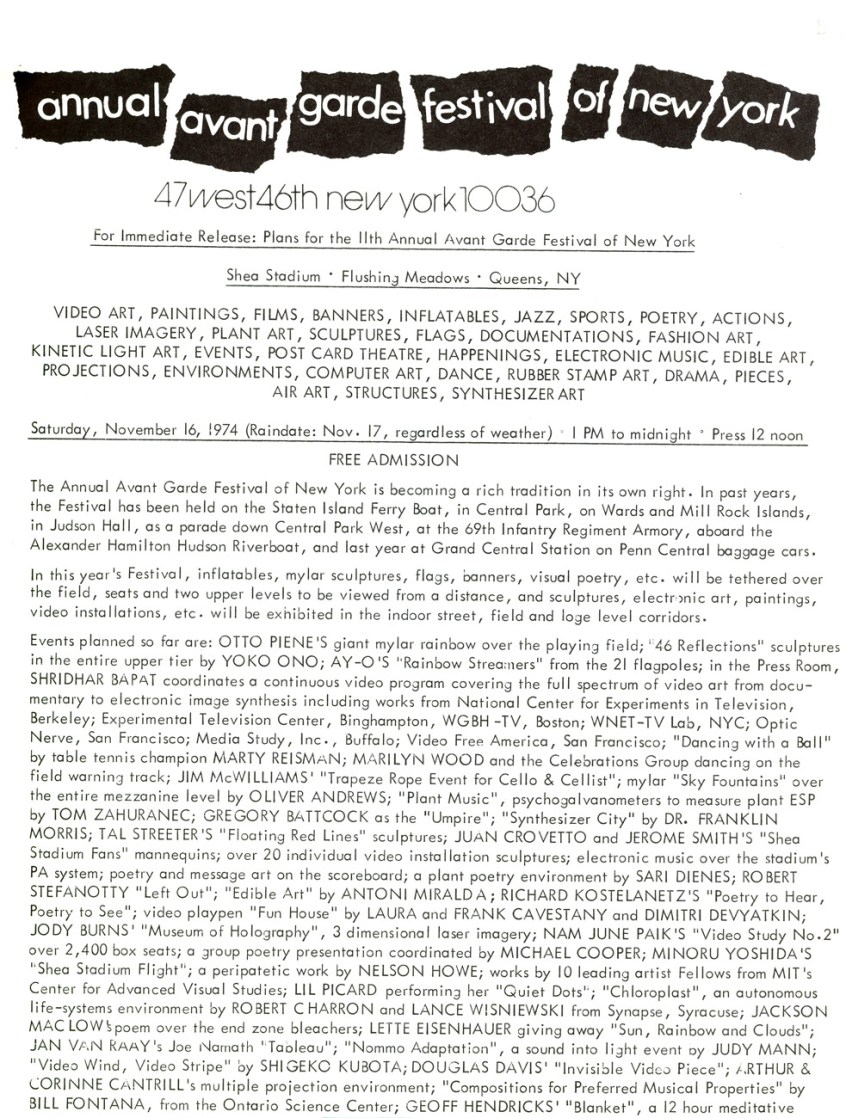

Press release for The 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1974

Program for The 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1974

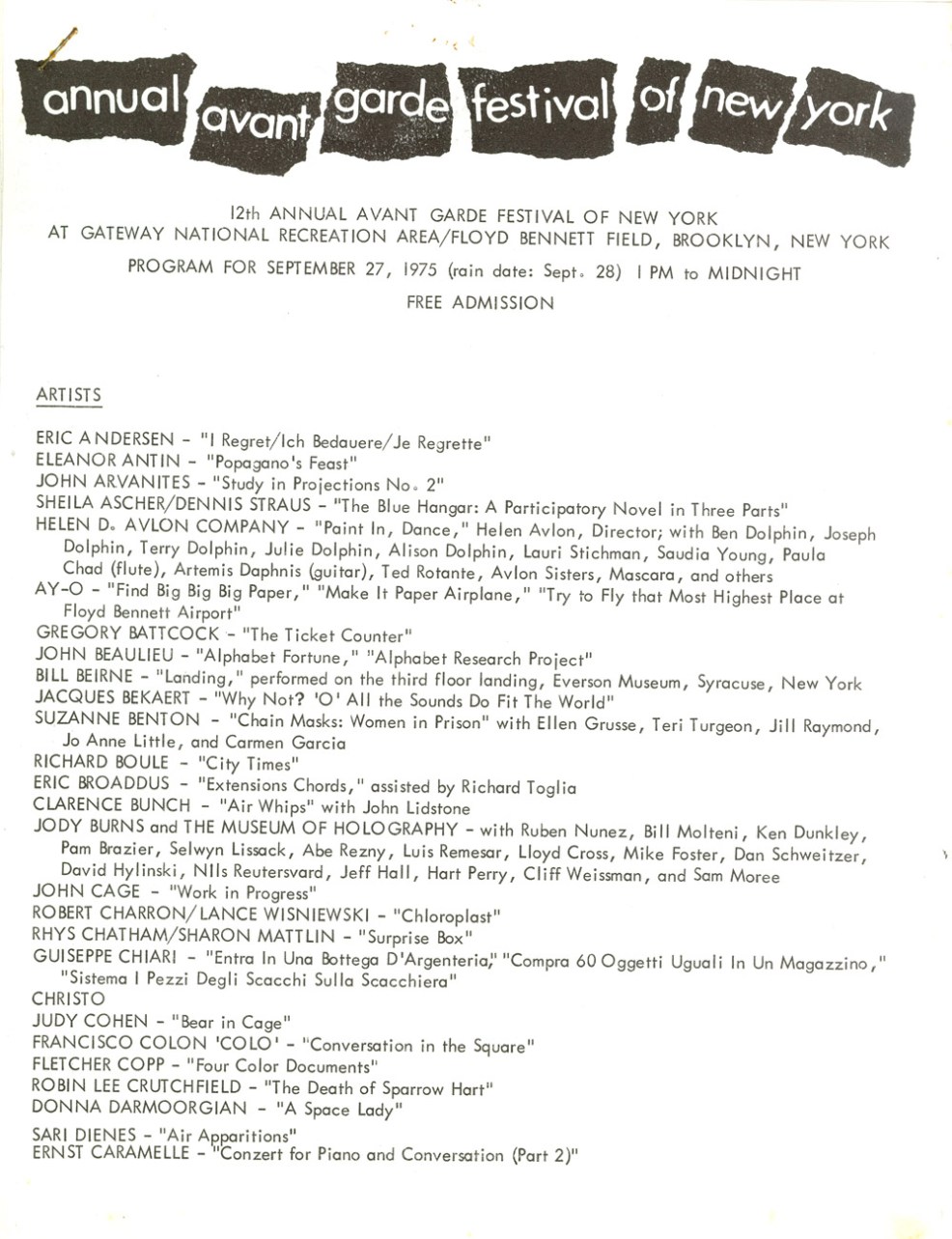

Program flyer from The 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1975

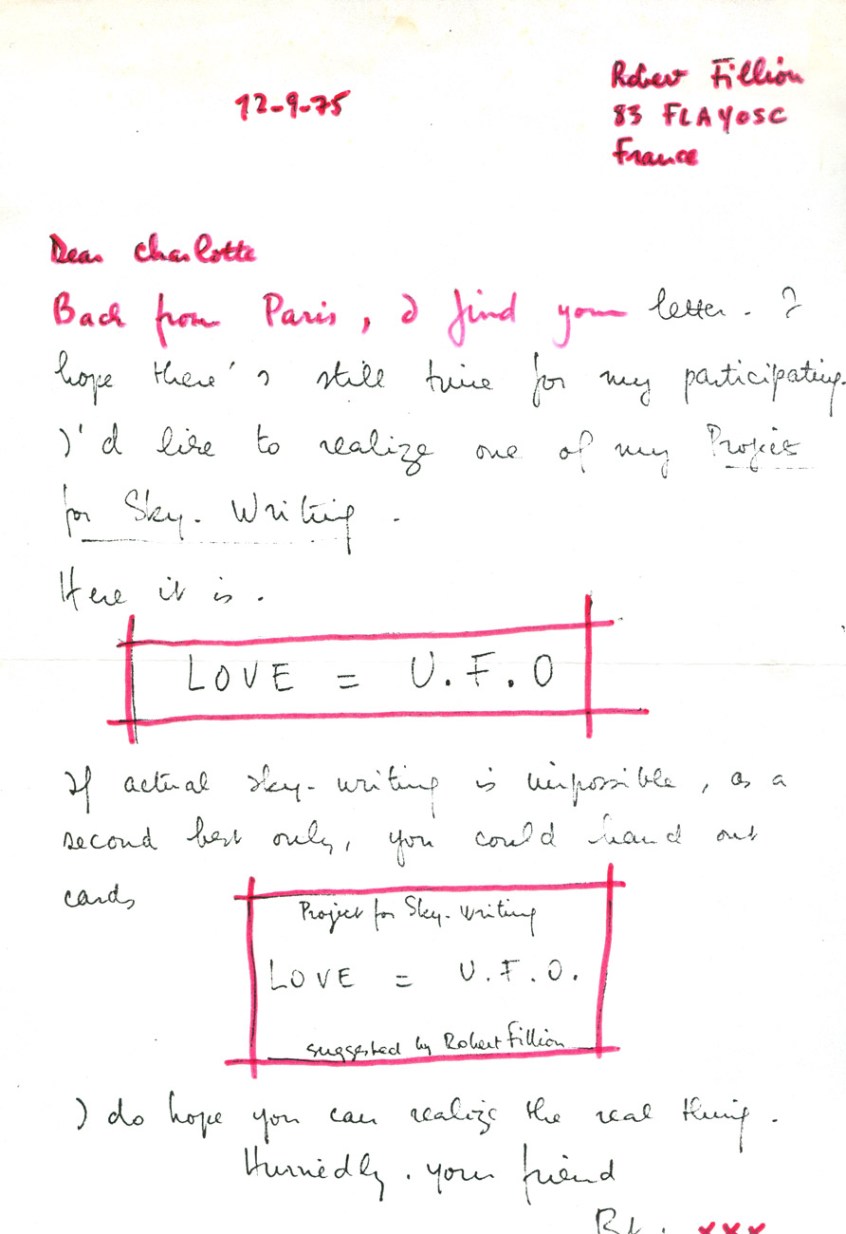

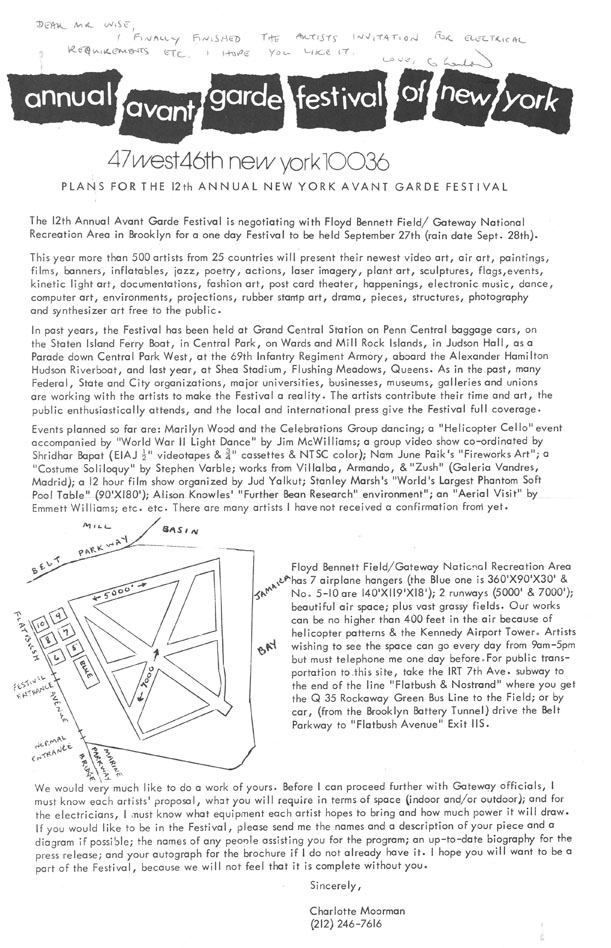

Plans / Artist invitation for The 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1975

Artist information for The 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1975

Press release for The 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1975

Plans for The 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1975

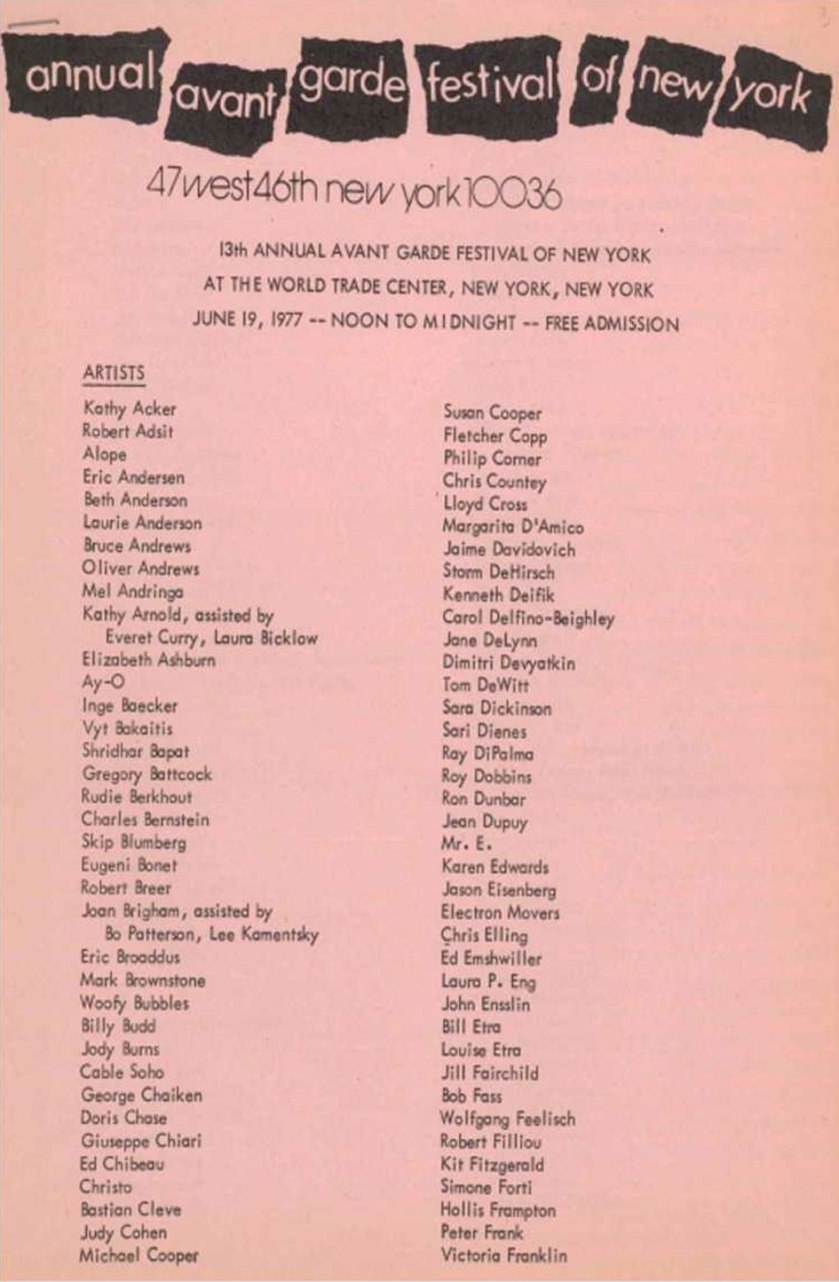

Program flyer from The 13th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1977

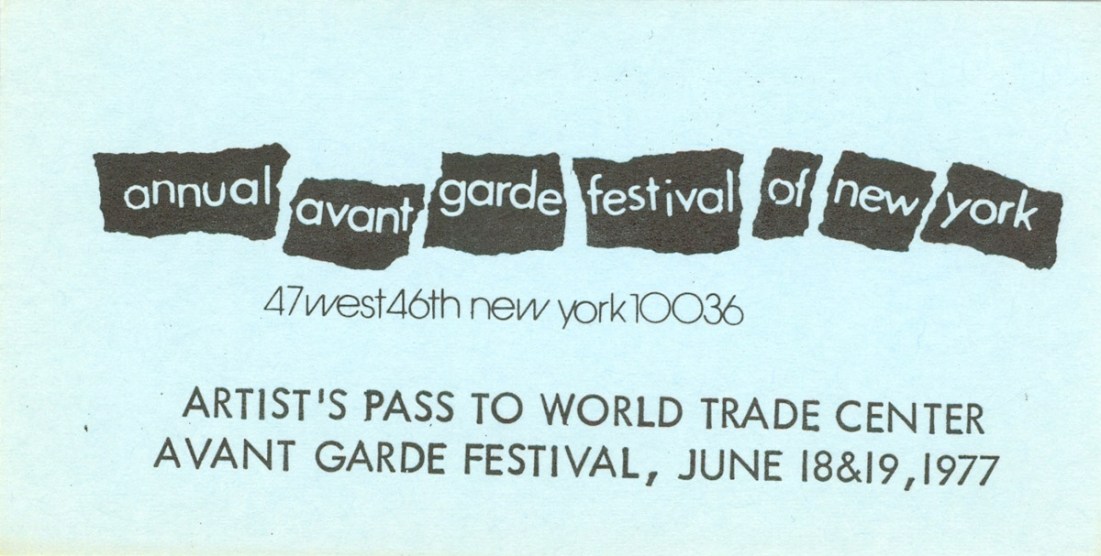

Artist pass for The 13th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1977

Program for The 13th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1977

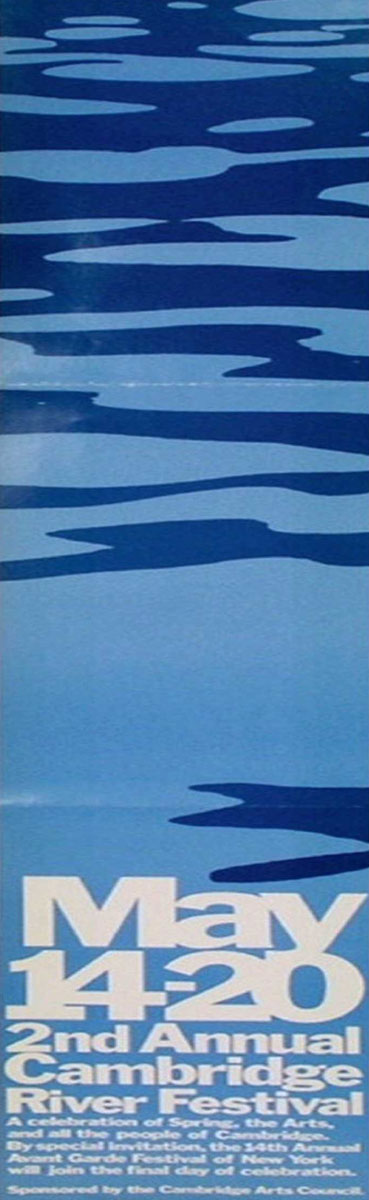

Program flyer from The 14th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1978

Program flyer from The 14th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1978

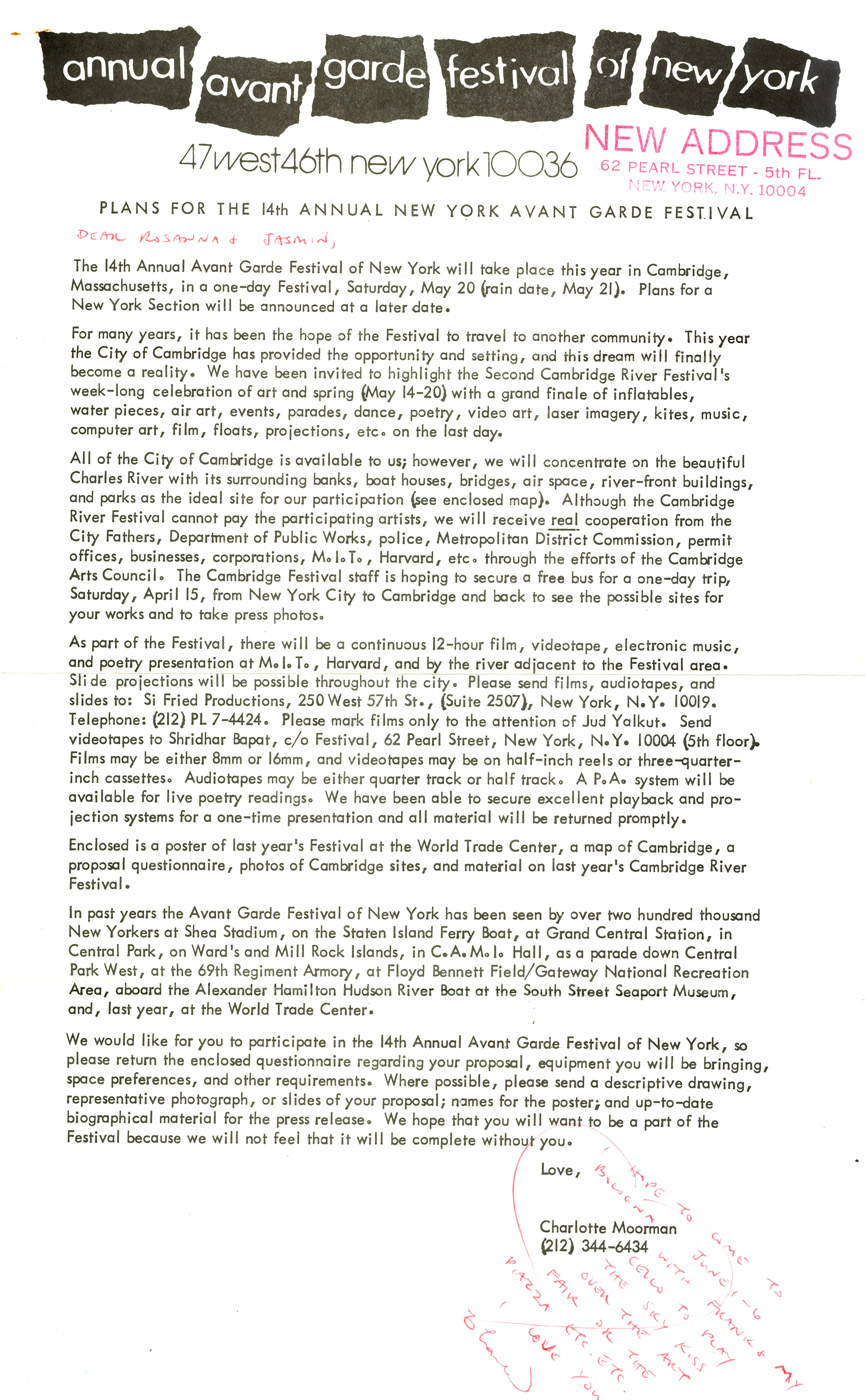

Press release for The 14th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1978

Press release for The 14th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1978

Plans for The 14th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1978

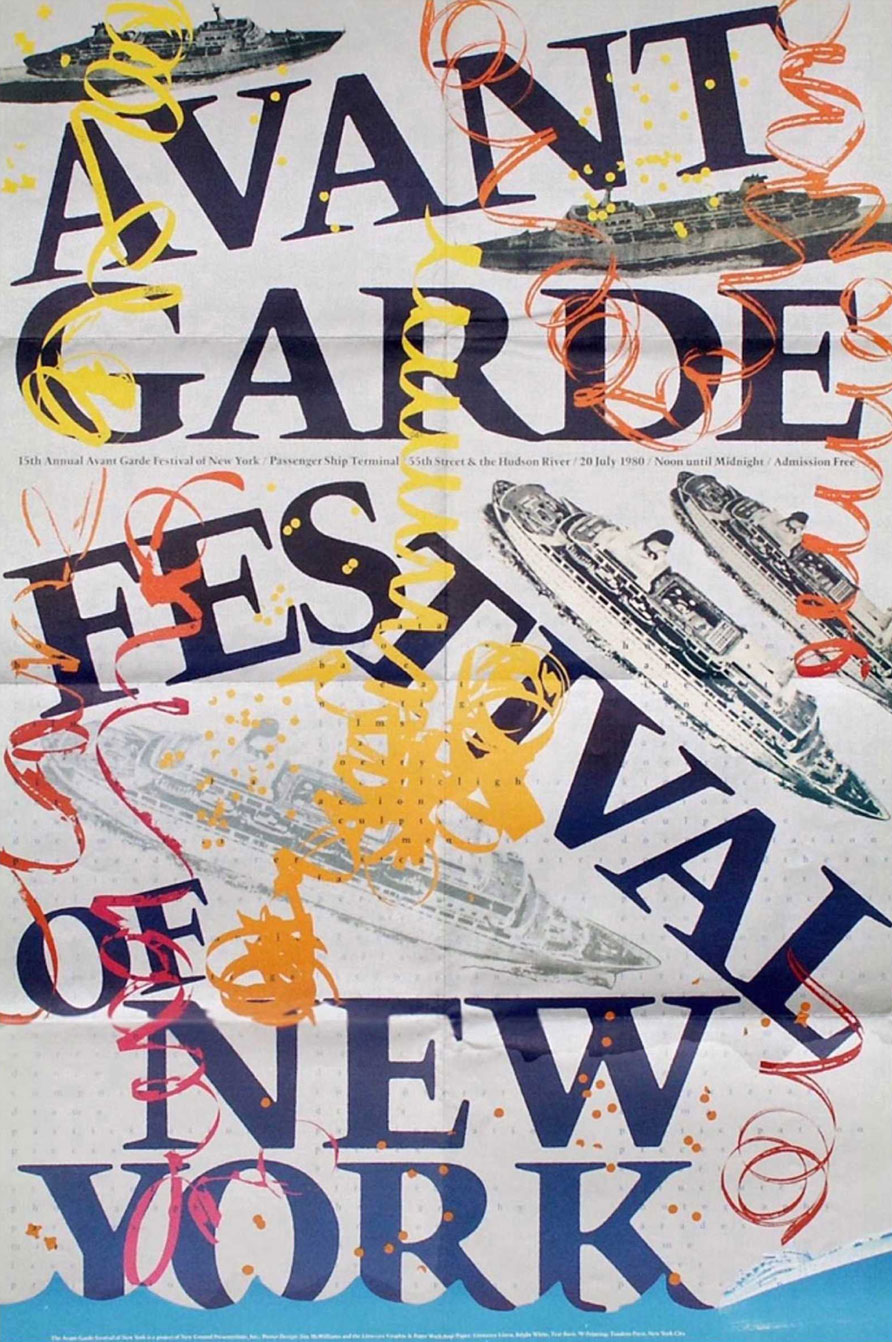

Program flyer from The 15th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1980

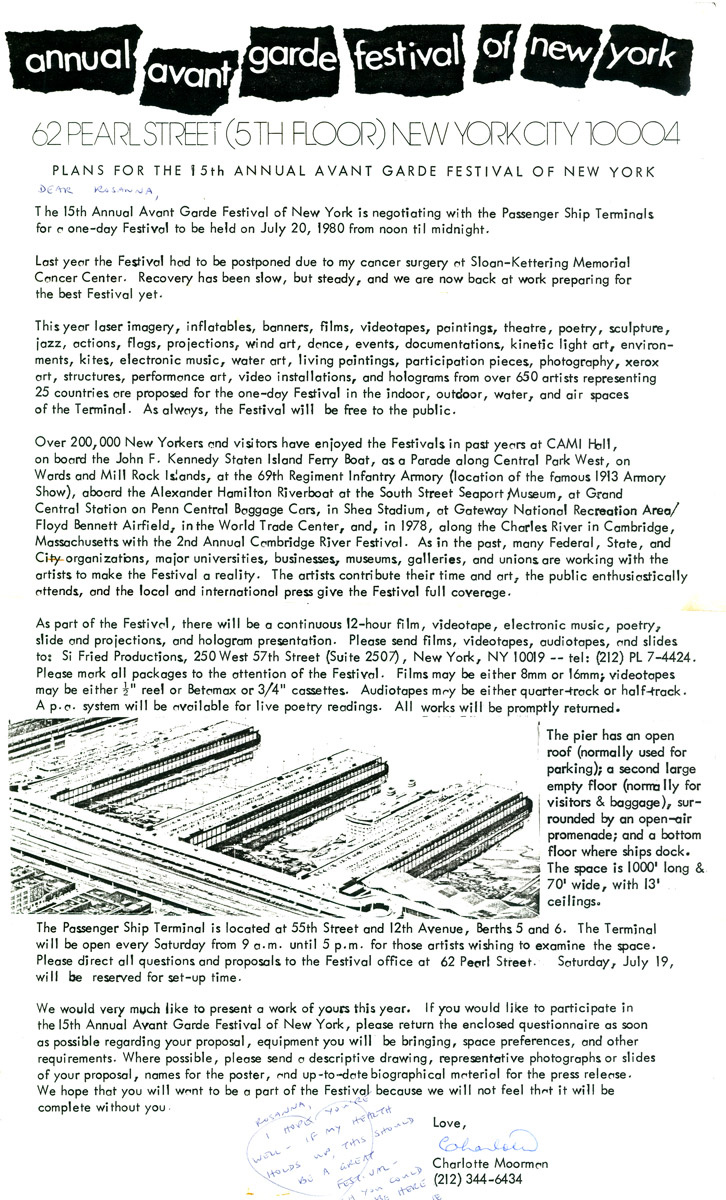

Press release for The 15th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1980

Press release for The 15th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1980

Artist information for The 15th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1980

Program for The 15th Annual Avant Garde Festival, 1980